Abbreviations

COVID-19

coronavirus disease 2019

COX-2

cyclooxygenase-2

DEAE-C

diethylaminoethyl cellulose

FTIR

fourier transform infrared spectroscopy

iNOS

inducible nitric oxide synthase

IL-6

interleukin-6

IL-1β

interleukin-1β

LPS

lipopolysaccharide

NMR

nuclear magnetic resonance

PGE2

prostaglandin E2

P/S

penicillin/streptomycin

TNF-α

tumor necrosis factor α

INTRODUCTION

Seaweeds continue to attract considerable attention in industrial and scientific fields because they serve as abundant sources of natural products, such as proteins, polysaccharides, lipids, and polyphenols, which are associated with antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and anti-cancer activities. Several bioactive compounds derived from seaweed have been identified (Mayer et al. 2019, Lee et al. 2020) and are potentially used for industrial and commercial purposes (Camacho et al. 2019). Therefore, the aquaculture of seaweeds is considered the most important sustainable bioresources. Some edible seaweeds including Pyropia, Undaria, and Saccharina species successfully cultivated (Hwang and Park 2020) and artificial seed production and cultivation techniques were also developed in Korea (Carrano et al. 2020, Ko et al. 2020).

Seaweed is a promising source of secondary metabolites and it has several advantages, such as high availability and low processing costs for industrial purposes compared with the land plant. Recently, brown algae have received great attention because of their bioactive compounds, especially the polysaccharide fucoidan, which contains an abundance of sulfate groups that exhibit various biological activities. Sulfated polysaccharides are major components of brown seaweed and exhibit various bioactivities, including anti-coagulant, antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, anti-cancer, anti-microbial, anti-viral, and hepatoprotective activities (Sanjeewa et al. 2018).

The functional food industry has become the most profitable and rapidly growing industry worldwide because of the increased concern for human health owing to coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). According to statistical reports, the global functional food market has been steadily growing, with the highest market share recorded in the United States (34.1%), China (15.1%), and the European Union (12.3%); the revenue of functional food products in the United States was 48,892 million USD in 2019 (KHSA 2021). Functional food products against immune and underlying diseases, including obesity, type 2 diabetes, and hypertension, have gained increased popularity in modern society. An early publication on food science and COVID-19 reported that specific dietary components and food supplements are important for the prevention of COVID-19 (Lange 2021). Therefore, the intake of functional foods is a good choice for managing human health during the COVID-19 pandemic. Recently, several synthetic COVID-19 treatments have been developed. However, these treatments evoke undesirable and severe side effects (e.g., fever, tiredness, headache, muscle ache, chills, diarrhea, pain, and redness). Management of the immune system is important to avoid undesirable side effects. Therefore, the sales of immune-related functional food products exponentially increased with the COVID-19 pandemic (Altun et al. 2021, Hamid et al. 2021).

The brown seaweed Ecklonia maxima belongs to the genus Ecklonia and is typically grown in Cape Town, South Africa (Rothman et al. 2006). Most studies have focused on ecological aspects (Crouch and Van Staden 1991, Anderson et al. 1997, Bolton et al. 2012) and efforts have been made to utilize the functional materials from E. maxima as biostimulants in agriculture (Stirk et al. 2014, Rengasamy et al. 2015). Seaweed hydrolysate and its functional ingredients are frequently used in the food and functional food industry. Earlier studies have revealed that fucoidan from E. maxima shows antioxidant and antidiabetic activities (Rengasamy et al. 2013, Daub et al. 2020). Wang et al. (2020) also reported various cosmeceutical activities, including antioxidant, anti-melanogenesis, and UV-protective activities, in vitro and in vivo (Wang et al. 2020). Enzyme-assisted hydrolysate from the stipe of E. maxima has antioxidant and anti-inflammatory potential (Lee et al. 2021). In this study, we purified fucoidan fractions from enzyme-assisted hydrolysate from E. maxima stipe and assessed its inhibitory activity on inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) and cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) expression using western blotting. We hypothesized that fucoidan from E. maxima possesses anti-inflammatory properties. The results of this study may contribute to the utilization of E. maxima in the functional food industry.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

Lipopolysaccharide and standard fucoidan were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM), fetal bovine serum (FBS), penicillin/streptomycin (P/S), and trypsin-EDTA solution were purchased from Welgene (Daegu, Korea). Pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as interleukin-6 (IL-6), tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α), and prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) were analyzed using a commercial colorimetric enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kit from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN, USA). Food-grade Viscozyme obtained from Novozyme (Copenhagen, Denmark).

Sample preparation and fucoidan purification via ion-exchange chromatography

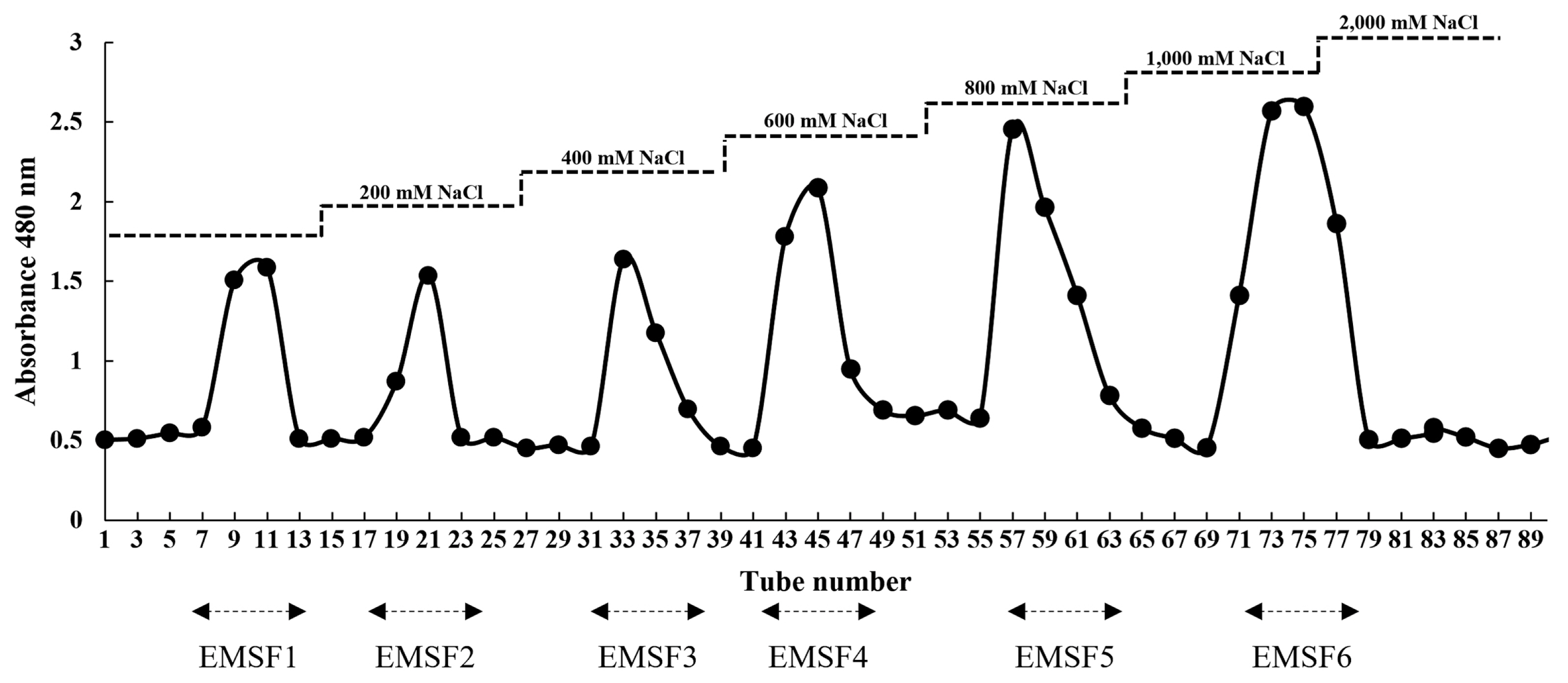

E. maxima stipe was kindly provided by the University of Cape Town, South Africa, and hydrolyzed using Viscozyme, as described by Lee et al. (2021). Briefly, 10 g of homogenized E. maxima stipe suspended in 1 L of distilled water and hydrolyzed with Viscozyme. After 24 h, the mixture was centrifuged (4°C, 12,000 rpm) and filtered. The filtrate was combined with double the volume of 95% EtOH and incubated at 4°C for 24 h. Twenty-four hours later, the precipitate was collected by centrifugation. The collected precipitate dried and homogenized using a grinder. The collected precipitate was named as crude polysaccharide. Then, the crude polysaccharide of Viscozyme-assisted hydrolysate from E. maxima stipe (EMSV) was purified using methods previously established by Jayawardena et al. (2020). For fucoidan purification, the crude polysaccharide was dissolved and filtered with a syringe filter (pore size, 0.45 μm) and introduced to diethylaminoethyl cellulose (DEAE-C), which was positively charged in sodium acetate buffer (50 mM). Fucoidan fractions were separated by gradient sodium chloride elution (50–2,000 mM). The separated fucoidan fractions were dialyzed to remove the remaining sodium and freeze-dried for in vitro experiments.

Proximate composition analysis

Association of Official Analytical Chemists methods were implemented to analyze the total carbohydrate, protein, polyphenol, and sulfate concentrations in fucoidans from E. maxima stipe (Horwitz et al. 1970).

Analysis of monosaccharide composition

The monosaccharide compositions were analyzed using high-performance anion-exchange chromatography with pulsed amperometric detection (Bio-LC System; Dionex, Sunnyvale, CA, USA) equipped with a CarboPac PA1 column (4.5 × 50 mm) and ED50 electrochemical detector (Dionex). All analytical fucoidan fractions were acid-hydrolyzed with 4 M trifluoroacetic acid. The acid hydrolysates were subjected to a separation column and the monosaccharide amount was calculated without considering the unhydrolyzed components.

Structural characterization by fourier transform infrared spectroscopy and 1H nuclear magnetic resonance analysis

Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectra of the fucoidan fraction and standard fucoidan were analyzed using an Alphall FTIR spectrometer (Bruker, Germany). The FTIR spectrum was analyzed in transmittance mode and wave number set in the range of 500–2,000 cm−1 wavenumber with optimal analytic conditions (transmittance mode, resolution: 4 cm−1, 24 scans). For proton nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) analysis, purified fucoidan was prepared by pre-saturation with deuterium oxide. Briefly, 1 mg of purified fucoidan was dissolved in deuterium oxide and transferred to an NMR tube. The prepared NMR tube was then subjected to a Bruker Avance 800 MHz NMR spectrometer (Bruker, Rheinstetten, Germany) with a magnetic field of 18.8 T. The 1H NMR spectrum was obtained using 64 scans, and the chemical shifts are given in ppm.

Cell culture

Murine macrophage cells (RAW 264.7) were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Rockville, MD, USA). RAW 264.7 cells were grown in DMEM containing 10% FBS and 1% P/S and periodically sub-cultured every two-day interval.

Evaluation of the nitric oxide inhibitory potential of fucoidan from Ecklonia maxima stipe

Nitric oxide (NO) inhibitory effects were assessed using the Griess assay, according to Sanjeewa et al. (2019). Briefly, RAW 264.7 cells were plated in 96-well plates at a concentration of 1 × 105 cells well−1 for 24 h. Then, the cells were treated with the samples 1 h before lipopolysaccharide (LPS) stimulation and incubated for 24 h in an incubator. After 24 h, 100 μL of cell culture medium was collected, mixed with Griess solution (2 mg mL−1), and incubated in the dark for 37°C, 10 min. NO production was measured at 500 nm using a Synergy HT Multi-Detection microplate reader (Bio-Tek, Winooski, VT, USA).

Measurement of pro-inflammatory cytokines

RAW 264.7 cells were plated as explained in 2.7, treated with samples 1 h before LPS stimulation, and incubated for an additional 24 h. After 24 h, the cell culture medium was retrieved and pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-6, TNF-α, and IL-1β) were analyzed using a commercial colorimetric kit following the manufacturer’s protocols.

Western blot analysis

Western blotting was performed according to the method described by Fernando et al. (Fernando et al. 2018). The amounts of activated iNOS and COX-2 proteins were evaluated, and images of western blots were taken using a FUSION SOLO Vilber Lourmat system (Paris, France). The intensities of the developed bands were quantified using ImageJ (version 1.4; National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA).

Statistical analysis

All measurements were analyzed in independent triplicate and presented as the mean ± standard deviation. Statistic evaluation was conducted using the statistical package for the GraphPad Prism (version 9.4.1; GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). p-values (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, and ****p < 0.0001 compared with the LPS-treated group; #p < 0.05, ##p < 0.01, ###p < 0.001, and ####p < 0.0001 compared with the LPS-untreated group) of <0.05 were considered significant.

RESULTS

Enzyme-assisted hydrolysis, fucoidan purification, and chemical composition analysis

Enzyme-mediated hydrolyzation was performed on E. maxima stipe, and Viscozyme-assisted hydrolysate was selected as a potential candidate for in vitro studies. In total, six fucoidan fractions were obtained via DEAE-C and anion-exchange chromatography, and the DEAE-C chromatogram is presented in Fig. 1. The chemical compositions of the fucoidan fractions are illustrated in Table 1. Accordingly, fucoidan fraction 6 of Viscozyme-assisted hydrolysate from E. maxima stipe (EMSF6) possessed the highest total carbohydrate (51.77 ± 0.47%) and sulfate contents (35.88 ± 0.36%), respectively. However, a low polyphenol content (0.15 ± 0.12%) was detected in EMSF6. The chemical composition (total polysaccharide, sulfate, and polyphenol) are summarized in Table 1.

Monosaccharide compositions of EMSFs

The monosaccharide contents were calculated by comparison with standard monosaccharide mixtures (fucose, rhamnose, arabinose, galactose, glucose, mannose, and fructose), and are tabulated in Table 2. The fucose and galactose contents exhibited an increasing trend during DEAE-C purification. However, other monosaccharides did not exhibit any particular trends.

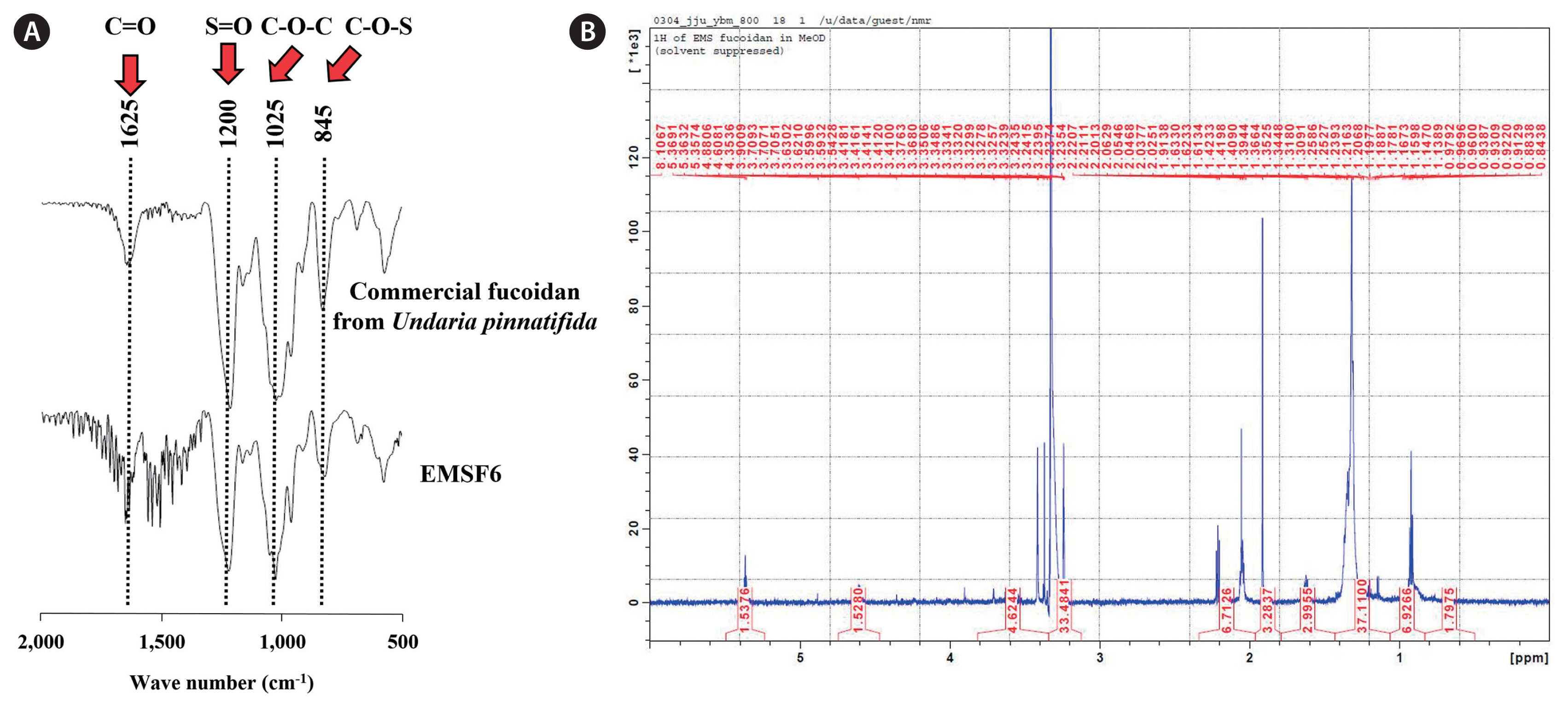

Determination of structural characters via FTIR and 1H NMR analysis

FTIR spectroscopy was performed on the EMSFs, and the IR spectrum was recorded in the range of 500–2,000 cm−1. The FTIR peak (840–845 cm−1) is attributed to a sulfate group substitution at the C-4 position, and the intense FTIR peak (1,025–1,035 cm−1) is attributed to the stretching of the C-O-C bond. The broad FTIR peak at 1,220–1,270 indicates sulfate groups (S=O). (Fig. 2A). The 1H NMR spectrum of the deuterium oxide exchange reaction of EMSF6 is shown in Fig. 2B. In the 1H NMR spectrum, a deuterium EtOH peak was observed at 2.0–2.2 ppm. The α-l-Fucf-(1→4) residues and methyl protons were detected at 0.9 and 1.3 ppm, respectively. The intense peak at 3.5–4.0 ppm is attributable to a sugar residue.

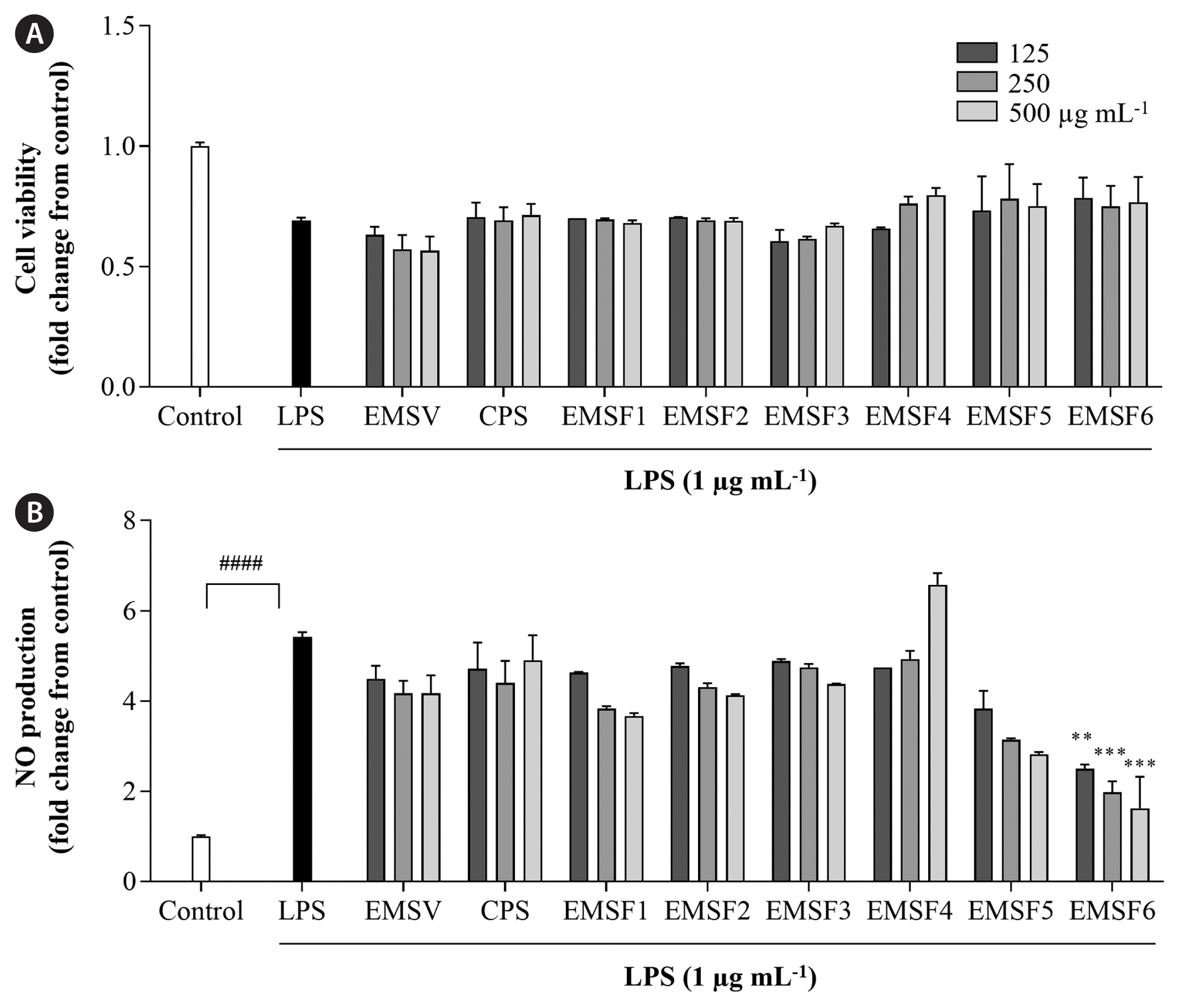

Potential anti-inflammatory effect of EMSFs in reducing LPS-induced inflammatory response in RAW 264.7 cells

The effects of EMSFs on LPS-induced cell viability and NO production are shown in Fig. 3. Cell viability significantly decreased, and NO production increased in LPS-induced RAW 264.7 cells compared with LPS-untreated groups. Treatment with EMSFs resulted in a recovery of cell viability and NO levels were significantly reduced by EMSF pre-treatment. Among the EMSFs, the EMSF6-treated group showed high cell viability and low NO production levels. The IC50 value of EMSF6 on NO production was recorded as 75.81 ± 7.55 μg mL−1. Therefore, EMSF6 was selected as a potential candidate for further in vitro studies.

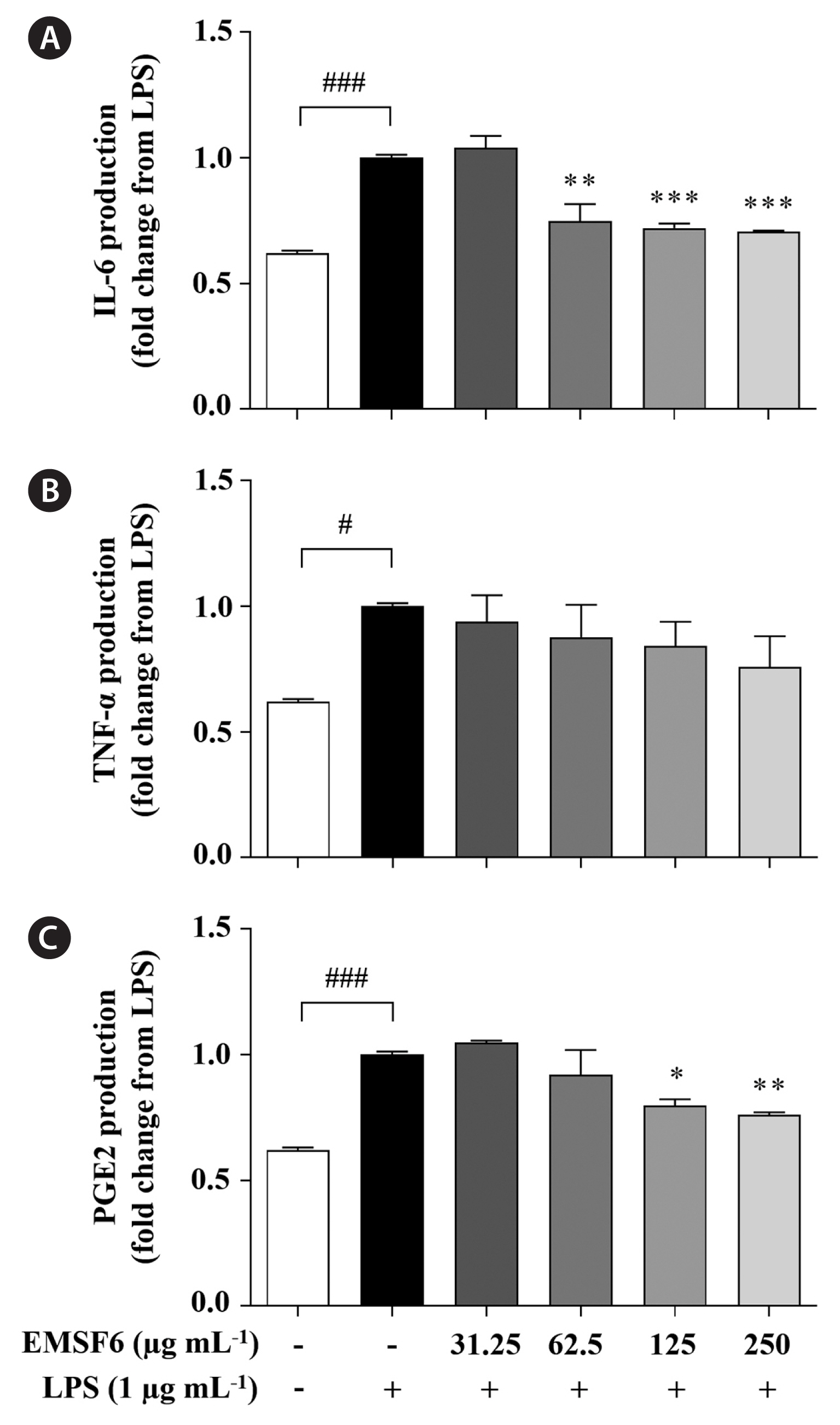

Effect of EMSF6 on inflammatory mediators in LPS-induced RAW 264.7 cells

Next, we investigated the inhibitory effects of EMSF6 on LPS-induced pro-inflammatory cytokine (IL-6, TNF-α, and PGE2) production. LPS treatment significantly increased the production of these pro-inflammatory cytokines (Fig. 4). However, EMSF6 significantly decreased the levels of those cytokines such as IL-6 and PGE2.

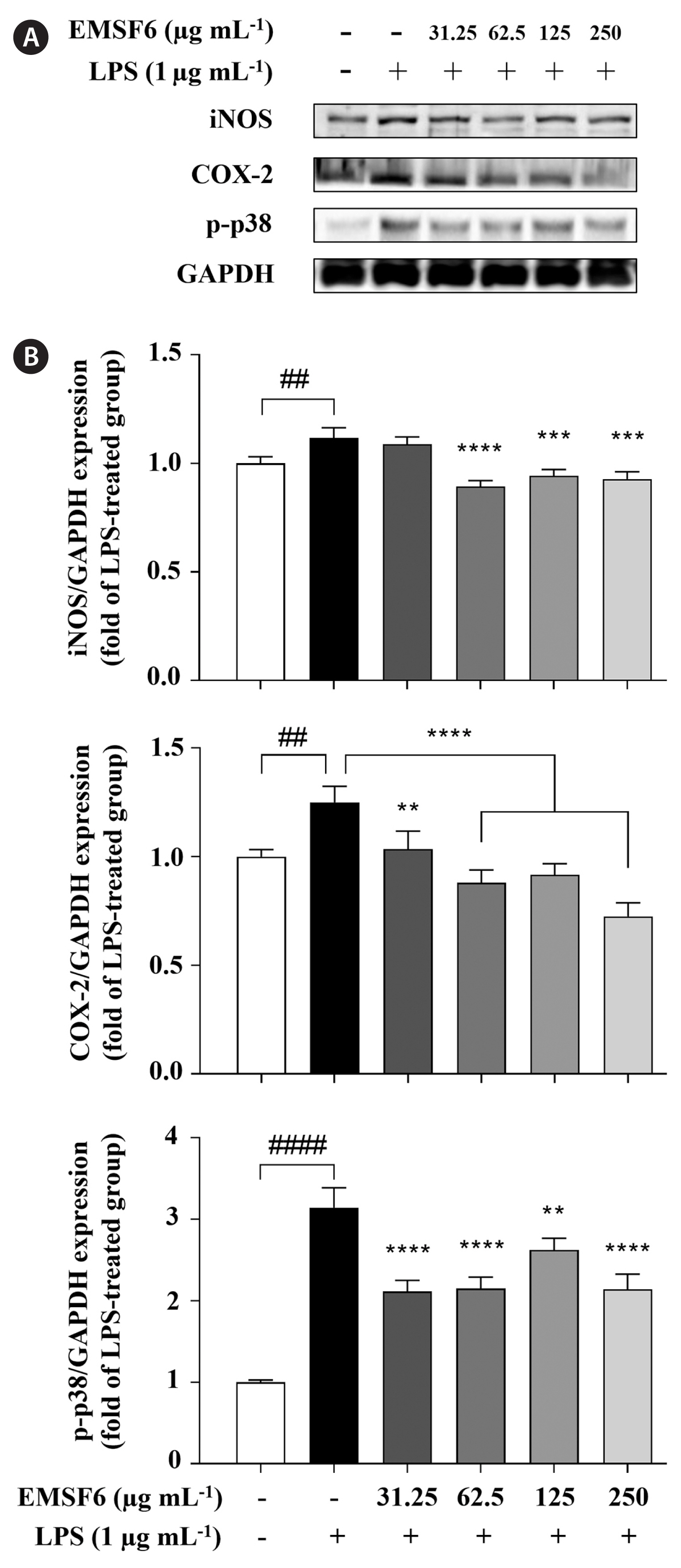

Potential of EMSF6 to inhibit LPS-induced iNOS, COX-2, and p-p38 protein expression

To elucidate the mechanisms underlying the anti-inflammatory effect of EMSF6, we analyzed the protein expression levels of iNOS and COX-2 using western blotting. Fig. 5A and B shows the protein expression bands of iNOS and COX-2 and their relative protein expression. LPS stimulated increases in iNOS, COX-2, and p-p38 expression. However, the levels of inflammatory iNOS and COX-2 proteins and the phosphorylation of p38 gradually decreased with EMSF6 treatment. These results indicate that EMSF6 effectively regulates major inflammatory mediators and proteins after LPS induction.

DISCUSSION

Fucoidan, a sulfated polysaccharide, is the most important functional ingredient found in brown seaweed and has a high sulfate and fucose content. Therefore, the abundance of fucoidan was indirectly calculated by measuring the fucose and sulfate content. Previous studies have reported that the bioactivities, mainly antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities, of fucoidans from different brown seaweeds are determined by the sulfate content (Jayawardena et al. 2019, Wang et al. 2019). Several studies have investigated the practical application of brown seaweed fucoidan in food or functional food products and for medical or pharmaceutical purposes (Citkowska et al. 2019, Fitton et al. 2019, Chen et al. 2021). Therefore, in the current study, we investigated the potential anti-inflammatory activity of fucoidans isolated from E. maxima stipe. In total, six fucoidans were obtained from E. maxima and their chemical / monosaccharide composition and anti-inflammatory potential were evaluated. Physical characteristics were determined by FTIR and 1H NMR spectroscopy. According to the chemical composition analysis, EMSFs consisted of a high polysaccharide and sulfate content and traceable amounts of protein and polyphenol. The monosaccharide composition results showed high fucose and galactose contents in EMSF6. These results demonstrate that fucose and galactose were highly concentrated during the purification step, which may be attributed to their potential anti-inflammatory activity. FTIR spectroscopy revealed that the purified EMSF6 showed FTIR spectrum patterns similar to those of commercial fucoidan. These results are solidified by previously published studies (Fernando et al. 2020, Wang et al. 2020). Additionally, 1H NMR results supported that EMSF6 has specific structural similarities with commercial fucoidans. Based on our structural determination and chemical / monosaccharide characterization, we estimated that EMSF6 is a fucoidan (Sanjeewa et al. 2019).

Pro-inflammatory cytokines are responsible for inflammation during tissue damage. Under these conditions, the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines and NO quickly increases, which increases the activation of immune-related cells to remove infected cells and sources of infection. In in vitro anti-inflammatory studies, EMSF6 showed the strongest NO inhibitory activity, and NO production was inhibited up to 1.62 ± 0.69-fold. Our previous study revealed that EMSV exhibits 4––4.5-fold NO inhibition compared with the LPS-untreated group (Lee et al. 2021). However, pro-inflammatory cytokines were also highly suppressed by EMSF6 compared with EMSV. Our findings demonstrated that the inhibitory activities on NO and pro-inflammatory cytokine production were increased by DEAE-C, and anion-exchange chromatography showed that purified fucoidan had higher NO inhibitory activity than EMSV. Based on our findings, we investigated the anti-inflammatory mechanism of EMSF6. In the pro-inflammatory cytokine analysis, IL-6 and PGE2 production were significantly decreased. Earlier studies have reported that COX-2 and iNOS support the decrease in the levels of these pro-inflammatory cytokines by regulation of immune-related gene expression (Liu et al. 2021, Yang et al. 2022). The current study indicated a significant downstream effect of iNOS and COX-2 in EMSF6 and LPS-treated RAW 264.7 cells. Collectively, our findings demonstrated that EMSF6 exhibited anti-inflammatory activity by regulating pro-inflammatory cytokines and protein expression of iNOS and COX-2 in LPS-induced RAW 264.7 cells.

Fucoidan from E. maxima stipe possesses potent anti-inflammatory activity by downregulating pro-inflammatory cytokines and suppressing protein expression of iNOS and COX-2 in LPS-induced RAW 264.7 cells. The results suggest that fucoidan from E. maxima stipe can be used as a functional ingredient in the food and functional food industry.