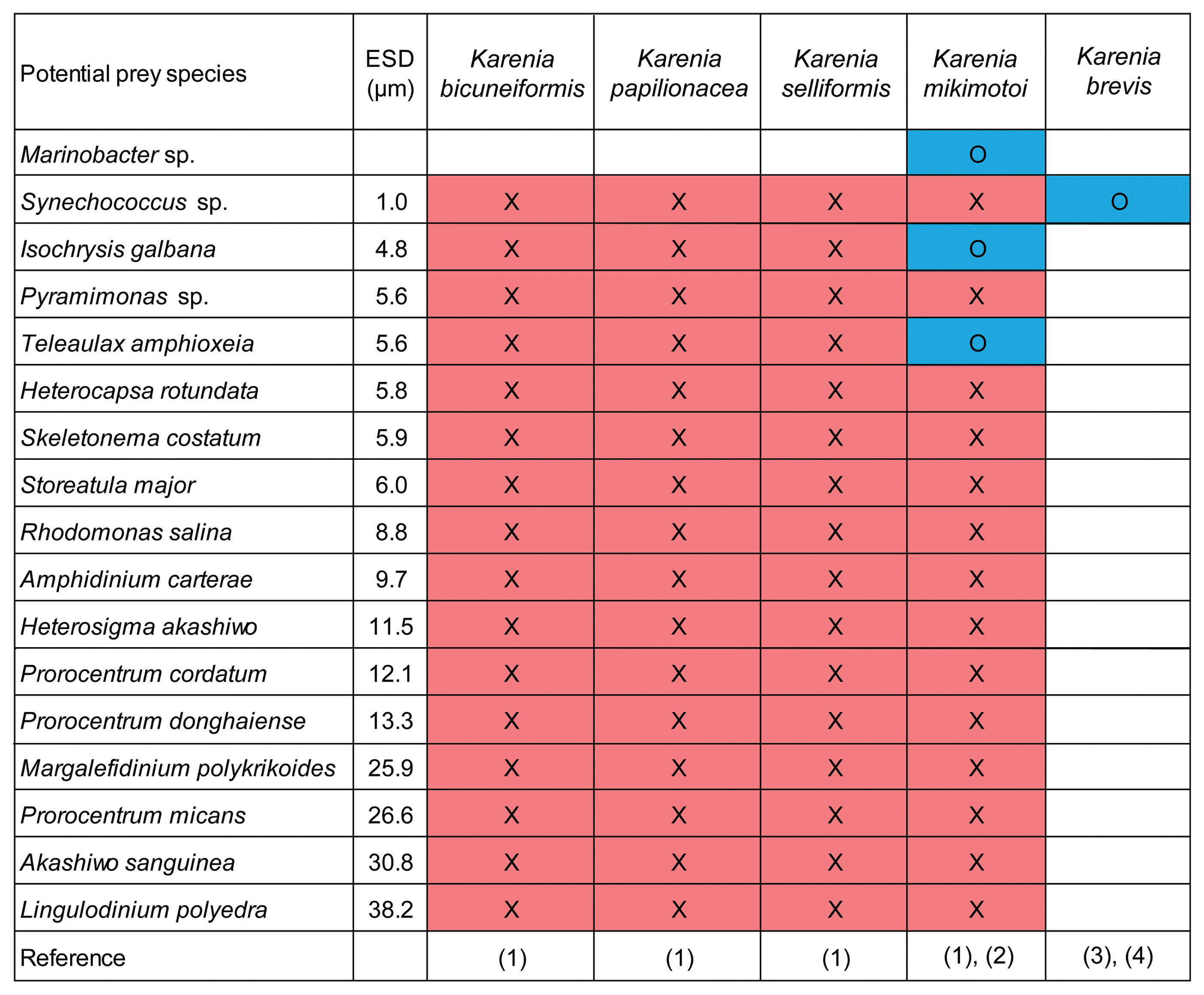

ABSTRACTExploring mixotrophy of dinoflagellate species is critical to understanding red-tide dynamics and dinoflagellate evolution. Some species in the dinoflagellate genus Karenia have caused harmful algal blooms. Among 10 Karenia species, the mixotrophic ability of only two species, Karenia mikimotoi and Karenia brevis, has been investigated. These species have been revealed to be mixotrophic; however, the mixotrophy of the other species should be explored. Moreover, although K. mikimotoi was previously known to be mixotrophic, only a few potential prey species have been tested. We explored the mixotrophic ability of Karenia bicuneiformis, Karenia papilionacea, and Karenia selliformis and the prey spectrum of K. mikimotoi by incubating them with 16 potential prey species, including a cyanobacterium, diatom, prymnesiophyte, prasinophyte, raphidophyte, cryptophytes, and dinoflagellates. Cells of K. bicuneiformis, K. papilionacea, and K. selliformis did not feed on any tested potential prey species, indicating a lack of mixotrophy. The present study newly discovered that K. mikimotoi was able to feed on the common cryptophyte Teleaulax amphioxeia. The phylogenetic tree based on the large subunit ribosomal DNA showed that the mixotrophic species K. mikimotoi and K. brevis belonged to the same clade, but K. bicuneiformis, K. papilionacea, and K. selliformis were divided into different clades. Therefore, the presence or lack of a mixotrophic ability in this genus may be partially related to genetic characterizations. The results of this study suggest that Karenia species are not all mixotrophic, varying from the results of previous studies.

INTRODUCTIONMixotrophic organisms conduct photosynthesis and uptake of external organic matters by phagotrophy or osmotrophy (Burkholder et al. 2008, Jeong et al. 2010b, Selosse et al. 2017, Stoecker et al. 2017). Exclusively photoautotrophic species are both primary producers and prey but mixotrophic species are primary producers, prey, and predators in food webs (Boraas et al. 1988, Jeong et al. 2010b, 2016, Ok et al. 2017). Mixotrophy elevates the growth rate of marine organisms and allows them to survive under inorganic nutrient depletion conditions (Park et al. 2006, Jeong et al. 2012, 2015, 2021, Kim et al. 2015). Therefore, determining the mixotrophic ability of a photosynthetic organism is fundamental for predicting its population dynamics and bloom formation in marine ecosystems (Jeong et al. 2015). Furthermore, determination of the presence or lack of mixotrophic ability and prey items has greatly improved our understanding of evolution in photosynthetic organisms (Jones 2000, Mansour and Anestis 2021). Therefore, exploring the mixotrophic ability of an organism is a crucial step regarding its ecology and evolution.

Dinoflagellates are a major group of eukaryotes in marine ecosystems, and many dinoflagellate species have been revealed to be mixotrophic (Bockstahler and Coats 1993, Stoecker et al. 1997, Li et al. 1999, Jeong et al. 2005b, 2016, 2021, Lee et al. 2016, Lim and Jeong 2021, Park et al. 2021). Thus, mixotrophy is a major trophic mode of dinoflagellates (Stoecker 1999, Jeong et al. 2010b). Many mixotrophic dinoflagellates have caused red tides or harmful algal blooms (HABs) in the global ocean (López-Cortés et al. 2019, Eom et al. 2021, Ok et al. 2021c, 2023, Sakamoto et al. 2021, Yñiguez et al. 2021), and feeding on diverse prey species by some mixotrophic dinoflagellates has possibly resulted in their global dominance (Jeong et al. 2021). Therefore, to better understand the ecological roles of dinoflagellates and predict their red tides or HABs, it is necessary to determine whether they are mixotrophic.

The dinoflagellate family Kareniaceae has been of major interest to scientists, aquaculture farmers, and government officers because many species in the family have caused HABs (Kempton et al. 2002, Adolf et al. 2008, Sengco 2009, Steidinger 2009, Van Dolah et al. 2009, Calbet et al. 2011, Siswanto et al. 2013, Lin et al. 2018, Ok et al. 2019, 2022, Zhang et al. 2022). This family includes six genera: Karenia, Karlodinium, Takayama, Asterodinium, Gertia, and Shimiella (Daugbjerg et al. 2000, de Salas et al. 2003, Bergholtz et al. 2006, Benico et al. 2019, Takahashi et al. 2019, Ok et al. 2021b). The species in the genus Karenia are distributed globally and have often caused red tides and HABs (Brand et al. 2012, Li et al. 2019, Liu et al. 2022). Several Karenia species have toxins, such as brevetoxin, gymnocin, and gymnodimine, and thus, are harmful to fish, invertebrates, birds, mammals, and humans (Baden 1989, Miles et al. 2003, Pierce et al. 2003, Brand et al. 2012, Fowler et al. 2015). Thus, predicting red-tide or HAB outbreaks caused by these Karenia species is critical to minimize economic losses due to red tides or HABs. The growth rate of a Karenia species is one of the most important parameters for establishing prediction models, and is primarily affected by its trophic mode, which could be exclusively autotrophic or mixotrophic (Jeong et al. 2015). However, among the 10 formally described Karenia species (Guiry and Guiry 2023), the mixotrophic ability of only two species, K. mikimotoi and K. brevis, has been tested; these two species have been revealed to be mixotrophic (Jeong et al. 2005a, Glibert et al. 2009, Zhang et al. 2011). However, it is also necessary to analyze the mixotrophic ability of the remaining eight species in the genus Karenia. Furthermore, although K. mikimotoi and K. brevis have been revealed to be mixotrophic, their feeding occurrence has only been tested on a few potential prey species (Jeong et al. 2005a, Zhang et al. 2011). To understand interactions between K. mikimotoi or K. brevis and common microalgal species, feeding occurrence by Karenia species on a diversity of common microalgal species should be investigated.

In the present study, we explored the mixotrophic ability of Karenia bicuneiformis (= Karenia bidigitata), Karenia papilionacea, and Karenia selliformis. Moreover, we investigated the feeding occurrence of K. mikimotoi on a cyanobacterium and diverse microalgal prey species that have not previously been tested. The results of this study may contribute to a better understanding of mixotrophy in Karenia, interactions between Karenia species and common microalgal species, dynamics of red tides and HABs caused by Karenia species, and the ecological roles of Karenia species in marine ecosystems.

MATERIALS AND METHODSExperimental organismsClonal cultures of K. bicuneiformis CAWD81 (= K. bidigitata), K. papilionacea CAWD91, K. selliformis NIES-4541, and K. mikimotoi NIES-2411 were obtained from the Cawthron Institute Culture Collection of Microalgae (New Zealand) and the National Institute for Environmental Studies (Japan). The cultures were transferred to 50 and 270-mL flasks containing L1 medium (Guillard and Hargraves 1993). These cultures were incubated at 20°C and 20 μmol photons m−2 s−1 using cool white fluorescent lights on a 14 : 10 h light/dark cycle.

Diverse phytoplankton species, including a cyanobacterium, diatom, prymnesiophyte, prasinophyte, raphidophyte, cryptophytes, and dinoflagellates, were provided as potential prey (Table 1). All potential prey species, except Synechococcus sp., Margalefidinium polykrikoides, and Lingulodinium polyedra, were grown at 20°C and 20–50 μmol photons m−2 s−1 on a 14 : 10 h light/dark cycle in enriched f/2 seawater medium (Guillard and Ryther 1962). Synechococcus sp. was incubated at 20°C under the dim light condition (≤10 μmol photons m−2 s−1) on a 14 : 10 h light/dark cycle in enriched f/2 seawater medium. M. polykrikoides and L. polyedra were incubated in enriched f/2 and L1 seawater medium, respectively (Guillard and Ryther 1962, Guillard and Hargraves 1993), at 20°C and 50 μmol photons m−2 s−1 under continuous illumination because they did not survive under a light/dark cycle (Lee et al. 2014).

Mixotrophic ability of Karenia speciesExperiments were designed to explore whether K. bicuneiformis CAWD81, K. papilionacea CAWD91, K. selliformis NIES-4541, and K. mikimotoi NIES-2411 were able to feed on target potential prey species when a diversity of prey items was provided. Five milliliters were removed from dense cultures of K. bicuneiformis, K. papilionacea, K. selliformis, and K. mikimotoi (ca. 3,000, 3,000, 3,000, and 20,000 cells mL−1, respectively) and then the cell density of the four Karenia species was determined using a compound microscope (BX53; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). The initial cell density of the tested Karenia species and each target potential prey species were established using an autopipette to deliver a predetermined volume of each culture to experimental 42-mL polycarbonate (PC) bottles (Table 1). A 42-mL PC bottle with a mixture of one Karenia species and one potential prey species, control of a potential prey species, and control of a Karenia species was set up for each target potential prey species. The bottles were filled to capacity with filtered seawater, capped, and placed on a vertically rotating wheel (0.9 r min−1). Each bottle, except that containing Synechococcus sp., M. polykrikoides, and L. polyedra, was incubated at 20°C and 20 μmol photons m−2 s−1 illumination under a 14 : 10 h light/dark cycle. Each bottle containing Synechococcus sp. was incubated at 20°C and 10 μmol photons m−2 s−1 illumination under a 14 : 10 h light/dark cycle. Each bottle containing M. polykrikoides and L. polyedra was incubated at 20°C and 50 μmol photons m−2 s−1 under continuous illumination.

After 2, 24, and 48 h, a total of ≥30 cells of each Karenia species was tracked to determine physical contact, attack (attempt to capture), and feeding (successful capture) with a dissecting microscope (SZX2-ILLB; Olympus) at 20–63× magnification. In this process, the lysis of the target potential prey species was also observed. Photographs of the tested Karenia species and each target potential prey species were taken on confocal dishes using a digital camera (Zeiss Axiocam 506; Carl Zeiss Ltd., Göttingen, Germany) on an inverted microscope (Zeiss Axiovert 200M; Carl Zeiss Ltd.) at 400–1,000× magnification.

To examine whether each Karenia species was able to feed on the cyanobacterium Synechococcus sp., the protoplasms of ≥100 Karenia cells were carefully observed after 2, 24, and 48-h incubation under the inverted epifluorescence microscope at a magnification of 1,000× (Zeiss Axiovert 200M; Carl Zeiss Ltd.). To observe whether K. mikimotoi NIES-2411 fed on the prymnesiophyte Isochrysis galbana, I. galbana cells were labeled with the fluorescent dye 5-([4,6-dichlorotriazin-2-yl]amino)fluorescein hydrochloride following the method of Rublee and Gallegos (1989).

Phylogenetic treeSequences of the large subunit ribosomal DNA (LSU rDNA) of Karenia species were obtained from GenBank. Sequences of the LSU rDNA of Karlodinium species as an outgroup were also obtained from GenBank. The sequences were aligned using MEGA v4 software (Tamura et al. 2007). The Bayesian and maximum likelihood analyses of the LSU rDNA region were conducted following Kang et al. (2010). The assumed empirical nucleotide frequencies of LSU rDNA comprised a substitution rate matrix with A–C substitutions = 0.0669, A–G = 0.1998, A–T = 0.0946, C–G = 0.0748, C–T = 0.4760, and G–T = 0.0879. Rates were assumed to follow a gamma distribution with a shape parameter of 0.5972 for variable sites. The proportion of sites assumed to be invariable was 0.4984.

RESULTSMixotrophic ability of three Karenia species

K. bicuneiformis CAWD81 did not feed on the cyanobacterium Synechococcus sp., prymnesiophyte Isochrysis galbana, prasinophyte Pyramimonas sp., diatom Skeletonema costatum, cryptophytes Rhodomonas salina, Storeatula major, and Teleaulax amphioxeia, raphidophyte Heterosigma akashiwo, and dinoflagellates Akashiwo sanguinea, Amphidinium carterae, Heterocapsa rotundata, L. polyedra, M. polykrikoides, Prorocentrum cordatum, Prorocentrum donghaiense, and Prorocentrum micans (Table 2, Fig. 1). Cells of K. bicuneiformis were observed to attack I. galbana and R. salina but did not feed on them. No lysis of K. bicuneiformis to the potential prey species was observed.

Among 16 potential prey species, K. papilionacea CAWD91 did not feed on any of the target potential prey species (Table 2, Fig. 2). Moreover, K. papilionacea did not attack any of them. No lysis of K. papilionacea to the potential prey species was observed.

K. selliformis NIES-4541 did not feed on any of the target potential prey species (Table 2, Fig. 3). Cells of K. selliformis were observed to attack I. galbana, S. major, Heterosigma akashiwo, and Heterocapsa rotundata but did not feed on them. Moreover, K. selliformis lysed cells of Pyramimonas sp., T. amphioxeia, and S. major (Fig. 4).

Feeding occurrence of Karenia mikimotoi

K. mikimotoi NIES-2411 was able to feed on the fluorescent-labeled I. galbana and live T. amphioxeia (Table 2, Fig. 5A–F). However, K. mikimotoi did not feed on the other potential prey species tested in this study (Table 2, Fig. 5G–I). Cells of K. mikimotoi were observed to attack R. salina, Heterosigma akashiwo, Amphidinium carterae, and P. micans, but did not feed on them. Moreover, K. mikimotoi lysed cells of Pyramimonas sp. and Akashiwo sanguinea (Fig. 6).

Phylogenetic analysisIn the phylogenetic tree based on the LSU rDNA of Karenia species, the mixotrophic species K. brevis and K. mikimotoi belonged to the same clade (Fig. 7). However, K. bicuneiformis, K. papilionacea, and K. selliformis, showing no mixotrophic ability, belonged to other clades in the phylogenetic tree.

DISCUSSIONPrior to the present study, all tested Karenia species were known to be mixotrophic; however, this included only two of the ten officially described species (Jeong et al. 2005a, Zhang et al. 2011, Guiry and Guiry 2023). The results of the present study clearly showed that three Karenia species tested in this study lack the mixotrophic ability. Thus, among the five Karenia species tested so far, more than half the species lack the mixotrophic ability (Fig. 8). The presence or lack of mixotrophy among the species in the genus Karenia implies evolutionary and ecological divergence. The mixotrophic ability of the five remaining Karenia species (i.e., K. asterichroma, K. brevisulcata, K. concordia, K. cristata, and K. longicanalis) should be explored.

Previously, K. mikimotoi was reported to feed on fluorescent microspheres (0.5–2.0 μm), the heterotrophic bacterium Marinobacter sp., and I. galbana (Zhang et al. 2011). The results of the present study clearly showed that K. mikimotoi can feed on T. amphioxeia (5.6 μm in equivalent spherical diameter) but not larger microalgal prey species. Thus, we suggested that K. mikimotoi can feed on the prey species <6 μm but not on larger-sized prey species. T. amphioxeia is commonly found in many marine environments (Jeong et al. 2013, Johnson et al. 2013, Cloern 2018, Gran-Stadniczeñko et al. 2019, Jang and Jeong 2020), and K. mikimotoi has a global distribution (Jeong et al. 2021). Thus, they have a high chance of encountering each other, and K. mikimotoi feeds on T. amphioxeia. This cryptophyte is a prey for many dinoflagellates, such as the mixotrophic dinoflagellates Biecheleria cincta, Gonyaulax polygramma, Gymnodinium aureolum, Heterocapsa steinii, Paragymnodinium shiwhaense, Prorocentrum cordatum, Prorocentrum donghaiense, Prorocentrum micans, M. polykrikoides, and Yihiella yeosuensis, the kleptoplasitidic dinoflagellates Pfiesteria piscicida and Shimiella gracilenta, and the heterotrophic dinoflagellates Gyrodiniellum shiwhaense and Luciella masanensis (Skovgaard 1998, Jeong et al. 2004, 2005b, 2005c, 2006, 2007, 2010a, 2011, Yoo et al. 2010, Kang et al. 2011, Johnson 2015, Jang et al. 2017, Ok et al. 2021a). Thus, K. mikimotoi may compete with diverse predators feeding on T. amphioxeia in marine environments.

Among the four Karenia species tested in the present study, K. selliformis and K. mikimotoi lysed some microalgal species, whereas K. bicuneiformis and K. papilionacea did not lyse any microalgal species. K. bicuneiformis, K. selliformis, and K. mikimotoi were reported to form blooms (e.g., Botes et al. 2003, Davidson et al. 2009, Li et al. 2019, Baohong et al. 2021, Orlova et al. 2022, Boudriga et al. 2023). Thus, K. selliformis and K. mikimotoi are likely to eliminate several microalgal species by lysis but not by feeding when they form blooms. The results of the present study showed that both K. selliformis and K. mikimotoi lysed Pyramimonas sp. However, K. selliformis lysed T. amphioxeia and Storeatula major that K. mikimotoi did not lyse. On the contrary, K. mikimotoi lysed Akashiwo sanguinea that K. selliformis did not lyse. Thus, this differential lysis may cause different selections of co-occurring microalgal species. Many studies reported allelopathic effects of K. mikimotoi on microalgal species; previously, cells or filtrates of K. mikimotoi were reported to inhibit the growth of the dinoflagellates Prorocentrum donghaiense, and Heterocapsa circularisquama, the chlorophyte Dunaliella salina, and the diatom Thalassiosira pseudonana (Uchida et al. 1999, Shen et al. 2015, He et al. 2016, Zheng et al. 2021). The results of the present study added Pyramimonas sp. and Akashiwo sanguinea to the lysed species of K. mikimotoi.

In the phylogenetic tree, mixotrophic K. mikimotoi and K. brevis belong to the same clade, whereas K. bicuneiformis, K. papilionacea, and K. selliformis, belong to different clades. Thus, the presence or lack of mixotrophy of Karenia species may be related to their genetic characterizations such as LSU rDNA. In the dinoflagellate genus Alexandrium, the presence and lack of mixotrophy was found in the species belonging to the same clade in the phylogenetic tree based on the LSU rDNA of Alexandrium (Lim et al. 2019). However, the mixotrophic ability of only five species of ten formally described Karenia species has been tested and included in this phylogenetic tree, whereas that of 16 species of 32 formally described Alexandrium species has been tested (Lim et al. 2019, Guiry and Guiry 2023). Thus, further analyses of Karenia species that have not been explored yet are needed to confirm if mixotrophy is affected by genetic characterizations.

In conclusion, the present study showed that some species in the genus Karenia are mixotrophic, but others are not. They may have different ecological niches and strategies for bloom formation in marine ecosystems. To better understand the structure and function of marine ecosystems, the presence or lack of mixotrophy of species in other genera should be explored.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTSThis research was supported by the National Research Foundation funded by the Ministry of Education (NRF-2022R1A6A3A01086348) award to JHO and the National Research Foundation by the Ministry of Science and ICT (NRF-2021M3I6A1091272; NRF-2021R1A2C1093379) award to HJJ.

Fig. 1Micrographs of Karenia bicuneiformis CAWD81 (Kb, black or white arrows) and potential prey species. Kb incubated with Synechococcus sp. (Syn, yellow arrows) taken under a light microscope (A) and epifluorescence microscope (B). (C) Intact Teleaulax amphioxeia (Ta, blue arrows). (D) Kb incubated with Ta (blue arrows). (E) Intact Pyramimonas sp. (Pyr, red arrows). (F) Kb incubated with Pyr (red arrows). (G) Intact Lingulodinium polyedra (Lp, green arrows). (H) Kb incubated with Lp (green arrows). No feeding of Kb on each potential prey species was observed. Scale bars represent: A–F, 10 μm; G & H, 20 μm.

Fig. 2Micrographs of Karenia papilionacea CAWD91 (Kp, black or white arrows) and potential prey species. Kp incubated with Synechococcus sp. (Syn, yellow arrows) taken under a light microscope (A) and epifluorescence microscope (B). A dashed arrow in (A) indicates the accumulation body (ab) of Kp (Haywood et al. 2004). (C) Intact Storeatula major (Sm, blue arrows). (D) Kp incubated with Sm (blue arrows). (E) Intact Heterosigma akashiwo (Ha, red arrows). (F) Kp incubated with Ha (red arrows). (G) Intact Amphidinium carterae (Ac, green arrows). (H) Kp incubated with Ac (green arrows). No feeding of Kp on each potential prey species was observed. Scale bars represent: A–H, 10 μm.

Fig. 3Micrographs of Karenia selliformis NIES-4541 (Ks, black or white arrows) and potential prey species. Ks incubated with Synechococcus sp. (Syn, yellow arrows) taken under a light microscope (A) and epifluorescence microscope (B). (C) Intact Skeletonema costatum (Sc, blue arrows). (D) Ks incubated with Sc (blue arrows). (E) Intact Heterosigma akashiwo (Ha, red arrows). (F) Ks incubated with Ha (red arrow). (G) Intact Prorocentrum micans (Pm, green arrows). (H) Ks incubated with Pm (green arrow). No feeding of Ks on each potential prey species was observed. Scale bars represent: A–F, 10 μm; G & H, 20 μm.

Fig. 4Micrographs of lysed microalgal species when being incubated with Karenia selliformis NIES-4541 (Ks, black arrows). (A) Intact Pyramimonas sp. (Pyr, blue arrowheads). (B) Ks and lysed Pyr (blue arrows). (C) Intact Teleaulax amphioxeia (Ta, red arrowheads). (D) Ks and lysed Ta (red arrows). (E) Intact Storeatula major (Sm, purple arrowheads). (F) Ks and lysed Sm (purple arrows). Scale bars represent: A–D, 5 μm; E & F, 10 μm.

Fig. 5Micrographs of Karenia mikimotoi NIES-2411 (Km, black or white arrows) and potential prey species. (A) Intact Isochrysis galbana (Ig, blue arrowheads). Km that fed on fluorescently-labeled Ig (FL-Ig, blue arrows) taken under a light (B) and epifluorescence microscope (C). (D) Intact Teleaulax amphioxeia (Ta, red arrowheads). Km that fed on a live Ta cell (red arrows) taken under a light (E) and epifluorescence microscope (F). (G) Km that did not feed on Rhodomonas salina (Rs, purple arrowheads). (H) Km that did not feed on Heterocapsa rotundata (Hr, orange arrowheads). (I) Km that did not feed on Margalefidinium polykrikoides (Mp, green arrowhead). Scale bars represent: A–F, 5 μm; G & H, 10 μm; I, 20 μm.

Fig. 6Micrographs of lysed microalgal species by Karenia mikimotoi NIES-2411 (Km, black arrows). (A) Intact Pyramimonas sp. (Pyr, blue arrowheads). (B) Km and lysed Pyr (blue arrows). (C) Intact Akashiwo sanguinea (As, red arrowheads). (D) Km and lysed As (red arrows). Scale bars represent: A & B, 5 μm; C & D, 20 μm.

Fig. 7Bayesian tree based on the large subunit ribosomal DNA region (847 bp), using a GTR + G + I model with the dinoflagellates Karlodinium armiger and Karlodinium australe as outgroup taxa. Numbers above or below the branches indicate the Bayesian posterior probability (left) and maximum likelihood bootstrap values (right). Posterior probabilities ≤0.5 are not shown. ○, presence of the mixotrophic ability; ×, lack of the mixotrophic ability.

Fig. 8Feeding by each Karenia species on diverse prey species. ○ in the blue box, fed by Karenia species; × in the red box, not fed by Karenia species. ESD, equivalent spherical diameter. 1, this study; 2, Zhang et al. (2011); 3, Jeong et al. (2005a); 4, Glibert et al. (2009).

Table 1Initial target density of each potential predator Karenia species and prey species Table 2Results of feeding occurrence test for four Karenia species in this study

REFERENCESAdolf, J. E., Bachvaroff, T. & Place, A. R. 2008. Can cryptophyte abundance trigger toxic Karlodinium veneficum blooms in eutrophic estuaries? Harmful Algae. 8:119–128.

Baohong, C., Kang, W., Huige, G. & Hui, L. 2021.

Karenia mikimotoi blooms in coastal waters of China from 1998 to 2017. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 249:107034 pp.

Benico, G., Takahashi, K., Lum, W. M. & Iwataki, M. 2019. Morphological variation, ultrastructure, pigment composition and phylogeny of the star-shaped dinoflagellate Asterodinium gracile (Kareniaceae, Dinophyceae). Phycologia. 58:405–418.

Bergholtz, T., Daugbjerg, N., Moestrup, Ø. & Fernández-Tejedor, M. 2006. On the identity of Karlodinium veneficum and description of Karlodinium armiger sp. nov. (Dinophyceae), based on light and electron microscopy, nuclear-encoded LSU rDNA, and pigment composition. J. Phycol.. 42:170–193.

Bockstahler, K. R. & Coats, D. W. 1993. Spatial and temporal aspects of mixotrophy in Chesapeake Bay dinoflagellates. J. Eukaryot. Microbiol.. 40:49–60.

Boraas, M. E., Estep, K. W., Johnson, P. W. & Sieburth, J. M. 1988. Phagotrophic phototrophs: the ecological significance of mixotrophy. J. Protozool.. 35:249–252.

Botes, L., Sym, S. D. & Pitcher, G. C. 2003.

Karenia cristata sp. nov. and Karenia bicuneiformis sp. nov. (Gymnodiniales, Dinophyceae): two new Karenia species from the South African coast. Phycologia. 42:563–571.

Boudriga, I., Abdennadher, M., Khammeri, Y., Mahfoudi, M., Quéméneur, M., Hamza, A., Bel Haj Hmida, N., Zouari, A. B. & Hassen, M. B. 2023.

Karenia selliformis bloom dynamics and growth rate estimation in the Sfax harbour (Tunisia), by using automated flow cytometry equipped with image in flow, during autumn 2019. Harmful Algae. 121:102366 pp.

Brand, L. E., Campbell, L. & Bresnan, E. 2012.

Karenia: the biology and ecology of a toxic genus. Harmful Algae. 14:156–178.

Burkholder, J. M., Glibert, P. M. & Skelton, H. M. 2008. Mixotrophy, a major mode of nutrition for harmful algal species in eutrophic waters. Harmful Algae. 8:77–93.

Calbet, A., Bertos, M., Fuentes-Grünewald, C., Alacid, E., Figueroa, R., Renom, B. & Garcés, E. 2011. Intraspecific variability in Karlodinium veneficum: growth rates, mixotrophy, and lipid composition. Harmful Algae. 10:654–667.

Cloern, J. E. 2018. Why large cells dominate estuarine phytoplankton. Limnol. Oceanogr.. 63:S392–S409.

Daugbjerg, N., Hansen, G., Larsen, J. & Moestrup, Ø. 2000. Phylogeny of some of the major genera of dinoflagellates based on ultrastructure and partial LSU rDNA sequence data, including the erection of three new genera of unarmoured dinoflagellates. Phycologia. 39:302–317.

Davidson, K., Miller, P., Wilding, T. A., Shutler, J., Bresnan, E., Kennington, K. & Swan, S. 2009. A large and prolonged bloom of Karenia mikimotoi in Scottish waters in 2006. Harmful Algae. 8:349–361.

de Salas, M. F., Bolch, C. J. S., Botes, L., Nash, G., Wright, S. W. & Hallegraeff, G. M. 2003.

Takayama gen. nov. (Gymnodiniales, Dinophyceae), a new genus of unarmored dinoflagellates with sigmoid apical grooves, including the description of two new species. J. Phycol.. 39:1233–1246.

Eom, S. H., Jeong, H. J., Ok, J. H., Park, S. A., Kang, H. C., You, J. H., Lee, S. Y., Yoo, Y. D., Lim, A. S. & Lee, M. J. 2021. Interactions between common heterotrophic protists and the dinoflagellate Tripos furca: implication on the long duration of its red tides in the South Sea of Korea in 2020. Algae. 36:25–36.

Fowler, N., Tomas, C., Baden, D., Campbell, L. & Bourdelais, A. 2015. Chemical analysis of Karenia papilionacea.

. Toxicon. 101:85–91.

Glibert, P. M., Burkholder, J. M., Kana, T. M., Alexander, J., Skelton, H. & Shilling, C. 2009. Grazing by Karenia brevis on Synechococcus enhances its growth rate and may help to sustain blooms. Aquat. Microb. Ecol.. 55:17–30.

Gran-Stadniczeñko, S., Egge, E., Hostyeva, V., Logares, R., Eikrem, W. & Edvardsen, B. 2019. Protist diversity and seasonal dynamics in Skagerrak plankton communities as revealed by metabarcoding and microscopy. J. Eukaryot. Microbiol.. 66:494–513.

Guillard, R. R. L. & Hargraves, P. E. 1993.

Stichochrysis immobilis is a diatom, not a chrysophyte. Phycologia. 32:234–236.

Guillard, R. R. & Ryther, J. H. 1962. Studies of marine planktonic diatoms: I. Cyclotella nana Hustedt, and Detonula confervacea (Cleve) Gran. Can. J. Microbiol.. 8:229–239.

Guiry, M. D. & Guiry, G. M. 2023. AlgaeBase. World-wide electronic publication. National University of Ireland, Galway, Available from: http://www. algaebase. org

. Accessed Jan 28, 2023

Haywood, A. J., Steidinger, K. A., Truby, E. W., Bergquist, P. R., Bergquist, P. L., Adamson, J. & Mackenzie, L. 2004. Comparative morphology and molecular phylogenetic analysis of three new species of the genus Karenia (Dinophyceae) from New Zealand. J. Phycol.. 40:165–179.

He, D., Liu, J., Hao, Q., Ran, L., Zhou, B. & Tang, X. 2016. Interspecific competition and allelopathic interaction between Karenia mikimotoi and Dunaliella salina in laboratory culture. Chin. J. Oceanol. Limnol.. 34:301–313.

Jang, S. H. & Jeong, H. J. 2020. Spatio-temporal distributions of the newly described mixotrophic dinoflagellate Yihiella yeosuensis (Suessiaceae) in Korean coastal waters and its grazing impact on prey populations. Algae. 35:45–59.

Jang, S. H., Jeong, H. J., Kwon, J. E. & Lee, K. H. 2017. Mixotrophy in the newly described dinoflagellate Yihiella yeosuensis: a small, fast dinoflagellate predator that grows mixotrophically, but not autotrophically. Harmful Algae. 62:94–103.

Jeong, H. J., Ha, J. H., Park, J. Y., Kim, J. H., Kang, N. S., Kim, S., Kim, J. S., Yoo, Y. D. & Yih, W. H. 2006. Distribution of the heterotrophic dinoflagellate Pfiesteria piscicida in Korean waters and its consumption of mixotrophic dinoflagellates, raphidophytes and fish blood cells. Aquat. Microb. Ecol.. 44:263–278.

Jeong, H. J., Ha, J. H., Yoo, Y. D., Park, J. Y., Kim, J. H., Kang, N. S., Kim, T. H., Kim, H. S. & Yih, W. H. 2007. Feeding by the Pfiesteria-like heterotrophic dinoflagellate Luciella masanensis

. J. Eukaryot. Microbiol.. 54:231–241.

Jeong, H. J., Kang, H. C., Lim, A. S., Jang, S. H., Lee, K., Lee, S. Y., Ok, J. H., You, J. H., Kim, J. H., Lee, K. H., Park, S. A., Eom, S. H., Yoo, Y. D. & Kim, K. Y 2021. Feeding diverse prey as an excellent strategy of mixotrophic dinoflagellates for global dominance. Sci. Adv. 7:eabe4214 pp.

Jeong, H. J., Lee, K. H., Yoo, Y. D., Kang, N. S. & Lee, K. 2011. Feeding by the newly described, nematocyst-bearing heterotrophic dinoflagellate Gyrodiniellum shiwhaense

. J. Eukaryot. Microbiol.. 58:511–524.

Jeong, H. J., Lim, A. S., Franks, P. J. S., Lee, K. H., Kim, J. H., Kang, N. S., Lee, M. J., Jang, S. H., Lee, S. Y., Yoon, E. Y., Park, J. Y., Yoo, Y. D., Seong, K. A., Kwon, J. E. & Jang, T. Y. 2015. A hierarchy of conceptual models of red-tide generation: nutrition, behavior, and biological interactions. Harmful Algae. 47:97–115.

Jeong, H. J., Ok, J. H., Lim, A. S., Kwon, J. E., Kim, S. J. & Lee, S. Y. 2016. Mixotrophy in the phototrophic dinoflagellate Takayama helix (family Kareniaceae): predator of diverse toxic and harmful dinoflagellates. Harmful Algae. 60:92–106.

Jeong, H. J., Park, J. Y., Nho, J. H., Park, M. O., Ha, J. H., Seong, K. A., Jeng, C., Seong, C. N., Lee, K. Y. & Yih, W. H. 2005a. Feeding by red-tide dinoflagellates on the cyanobacterium Synechococcus

. Aquat. Microb. Ecol.. 41:131–143.

Jeong, H. J., Yoo, Y. D., Kang, N. S., Lim, A. S., Seong, K. A., Lee, S. Y., Lee, M. J., Lee, K. H., Kim, H. S., Shin, W., Nam, S. W., Yih, W. & Lee, K. 2012. Heterotrophic feeding as a newly identified survival strategy of the dinoflagellate Symbiodinium

. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A.. 109:12604–12609.

Jeong, H. J., Yoo, Y. D., Kang, N. S., Rho, J. R., Seong, K. A., Park, J. W., Nam, G. S. & Yih, W. 2010a. Ecology of Gymnodinium aureolum. I. Feeding in western Korean waters. Aquat. Microb. Ecol.. 59:239–255.

Jeong, H. J., Yoo, Y. D., Kim, J. S., Kim, T. H., Kim, J. H., Kang, N. S. & Yih, W. 2004. Mixotrophy in the phototrophic harmful alga Cochlodinium polykrikoides (Dinophycean): prey species, the effects of prey concentration, and grazing impact. J. Eukaryot. Microbiol.. 51:563–569.

Jeong, H. J., Yoo, Y. D., Kim, J. S., Seong, K. A., Kang, N. S. & Kim, T. H. 2010b. Growth, feeding and ecological roles of the mixotrophic and heterotrophic dinoflagellates in marine planktonic food webs. Ocean Sci. J.. 45:65–91.

Jeong, H. J., Yoo, Y. D., Lee, K. H., Kim, T. H., Seong, K. A., Kang, N. S., Lee, S. Y., Kim, J. S., Kim, S. & Yih, W. H. 2013. Red tides in Masan Bay, Korea in 2004–2005: I. Daily variations in the abundance of red-tide organisms and environmental factors. Harmful Algae. 30(Suppl 1):S75–S88.

Jeong, H. J., Yoo, Y. D., Park, J. Y., Song, J. Y., Kim, S. T., Lee, S. H., Kim, K. W. & Yih, W. H. 2005b. Feeding by phototrophic red-tide dinoflagellates: five species newly revealed and six species previously known to be mixotrophic. Aquat. Microb. Ecol.. 40:133–150.

Jeong, H. J., Yoo, Y. D., Seong, K. A., Kim, J. H., Park, J. Y., Kim, S., Lee, S. H., Ha, J. H. & Yih, W. H. 2005c. Feeding by the mixotrophic dinoflagellate Gonyaulax polygramma: mechanisms, prey species, effects of prey concentration, and grazing impact. Aquat. Microb. Ecol.. 38:249–257.

Johnson, M. D. 2015. Inducible mixotrophy in the dinoflagellate Prorocentrum minimum

. J. Eukaryot. Microbiol.. 62:431–443.

Johnson, M. D., Stoecker, D. K. & Marshall, H. G. 2013. Seasonal dynamics of Mesodinium rubrum in Chesapeake Bay. J. Plankton Res.. 35:877–893.

Kang, N. S., Jeong, H. J., Moestrup, Ø., Shin, W., Nam, S. W., Park, J. Y., de Salas, M. F., Kim, K. W. & Noh, J. H. 2010. Description of a new planktonic mixotrophic dinoflagellate Paragymnodinium shiwhaense n. gen. , n. sp. from the coastal waters off western Korea: morphology, pigments, and ribosomal DNA gene sequence. J. Eukaryot. Microbiol.. 57:121–144.

Kang, N. S., Jeong, H. J., Yoo, Y. D., Yoon, E. Y., Lee, K. H., Lee, K. & Kim, G. 2011. Mixotrophy in the newly described phototrophic dinoflagellate Woloszynskia cincta from western Korean waters: feeding mechanism, prey species and effect of prey concentration. J. Eukaryot. Microbiol.. 58:152–170.

Kempton, J. W., Lewitus, A. J., Deeds, J. R., Law, J. M. & Place, A. R. 2002. Toxicity of Karlodinium micrum (Dinophyceae) associated with a fish kill in a South Carolina brackish retention pond. Harmful Algae. 1:233–241.

Kim, S., Yoon, J. & Park, M. G. 2015. Obligate mixotrophy of the pigmented dinoflagellate Polykrikos lebourae (Dinophyceae, Dinoflagellata). Algae. 30:35–47.

Lee, K. H., Jeong, H. J., Jang, T. Y., Lim, A. S., Kang, N. S., Kim, J. -H., Kim, K. Y., Park, K. -T. & Lee, K. 2014. Feeding by the newly described mixotrophic dinoflagellate Gymnodinium smaydae: feeding mechanism, prey species, and effect of prey concentration. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol.. 459:114–125.

Lee, K. H., Jeong, H. J., Kwon, J. E., Kang, H. C., Kim, J. H., Jang, S. H., Park, J. Y., Yoon, E. Y. & Kim, J. S. 2016. Mixotrophic ability of the phototrophic dinoflagellates Alexandrium andersonii, A. affine, and A. fraterculus.

. Harmful Algae. 59:67–81.

Li, A., Stoecker, D. K. & Adolf, J. E. 1999. Feeding, pigmentation, photosynthesis and growth of the mixotrophic dinoflagellate Gyrodinium galatheanum

. Aquat. Microb. Ecol.. 19:163–176.

Li, X., Yan, T., Yu, R. & Zhou, M. 2019. A review of Karenia mikimotoi: bloom events, physiology, toxicity and toxic mechanism. Harmful Algae. 90:101702 pp.

Lim, A. S., Jeong, H. J. & Ok, J. H. 2019. Five Alexandrium species lacking mixotrophic ability. Algae. 34:289–301.

Lin, C. -H. M, Lyubchich, V. & Glibert, P. M. 2018. Time series models of decadal trends in the harmful algal species Karlodinium veneficum in Chesapeake Bay. Harmful Algae. 73:110–118.

Liu, C., Zhang, X. & Wang, X. 2022. DNA metabarcoding data reveals harmful algal-bloom species undescribed previously at the northern Antarctic Peninsula region. Polar Biol.. 45:1495–1512.

López-Cortés, D. J., Núñez Vázquez, E. J., Dorantes-Aranda, J. J., Band-Schmidt, C. J., Hernández-Sandoval, F. E., Bustillos-Guzmán, J. J., Leyva-Valencia, I. & Fernández-Herrera, L. J. 2019. The state of knowledge of harmful algal blooms of Margalefidinium polykrikoides (aka Cochlodinium polykrikoides) in Latin America. Front. Mar. Sci. 6:463 pp.

Mansour, J. S. & Anestis, K. 2021. Eco-evolutionary perspectives on mixoplankton. Front. Mar. Sci.. 8:666160 pp.

Miles, C. O., Wilkins, A. L., Stirling, D. J. & MacKenzie, A. L. 2003. Gymnodimine C, an isomer of gymnodimine B, from Karenia selliformis

. J. Agric. Food Chem.. 51:4838–4840.

Ok, J. H., Jeong, H. J., Kang, H. C., Park, S. A., Eom, S. H., You, J. H. & Lee, S. Y. 2021a. Ecophysiology of the kleptoplastidic dinoflagellate Shimiella gracilenta: I. spatiotemporal distribution in Korean coastal waters and growth and ingestion rates. Algae. 36:263–283.

Ok, J. H., Jeong, H. J., Kang, H. C., Park, S. A., Eom, S. H., You, J. H. & Lee, S. Y. 2022. Ecophysiology of the kleptoplastidic dinoflagellate Shimiella gracilenta: II. Effects of temperature and global warming. Algae. 37:49–62.

Ok, J. H., Jeong, H. J., Lee, S. Y., Park, S. A. & Noh, J. H 2021b.

Shimiella gen. nov. and Shimiella gracilenta sp. nov. (Dinophyceae, Kareniaceae), a kleptoplastidic dinoflagellate from Korean waters and its survival under starvation. J. Phycol.. 57:70–91.

Ok, J. H., Jeong, H. J., Lim, A. S. & Lee, K. H. 2017. Interactions between the mixotrophic dinoflagellate Takayama helix and common heterotrophic protists. Harmful Algae. 68:178–191.

Ok, J. H., Jeong, H. J., Lim, A. S., You, J. H., Kang, H. C., Kim, S. J. & Lee, S. Y. 2019. Effects of light and temperature on the growth of Takayama helix (Dinophyceae): mixotrophy as a survival strategy against photoinhibition. J. Phycol.. 55:1181–1195.

Ok, J. H., Jeong, H. J., Lim, A. S., You, J. H., Yoo, Y. D., Kang, H. C., Park, S. A., Lee, M. J. & Eom, S. H 2023. Effects of intrusion and retreat of deep cold waters on the causative species of red tides offshore in the South Sea of Korea. Mar. Biol.. 170:6 pp.

Ok, J. H., Jeong, H. J., You, J. H., Kang, H. C., Park, S. A., Lim, A. S., Lee, S. Y. & Eom, S. H 2021c. Phytoplankton bloom dynamics in incubated natural seawater: predicting bloom magnitude and timing. Front. Mar. Sci. 8:681252 pp.

Orlova, T. Y., Aleksanin, A. I., Lepskaya, E. V., Efimova, K. V., Selina, M. S., Morozova, T. V., Stonik, I. V., Kachur, V. A., Karpenko, A. A., Vinnikov, K. A., Adrianov, A. V. & Iwataki, M. 2022. A massive bloom of Karenia species (Dinophyceae) off the Kamchatka coast, Russia, in the fall of 2020. Harmful Algae. 120:102337 pp.

Park, M. G., Kim, S., Kim, H. S., Myung, G., Kang, Y. G. & Yih, W. 2006. First successful culture of the marine dinoflagellate Dinophysis acuminata

. Aquat. Microb. Ecol.. 45:101–106.

Park, S. A., Jeong, H. J., Ok, J. H., Kang, H. C., You, J. H., Eom, S. H., Yoo, Y. D. & Lee, M. J. 2021. Bioluminescence capability and intensity in the dinoflagellate Alexandrium species. Algae. 36:299–314.

Pierce, R. H., Henry, M. S., Blum, P. C., Lyons, J., Cheng, Y. S., Yazzie, D. & Zhou, Y. 2003. Brevetoxin concentrations in marine aerosol: human exposure levels during a Karenia brevis harmful algal bloom. Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol.. 70:161–165.

Rublee, P. A. & Gallegos, C. L. 1989. Use of fluorescently labelled algae (FLA) to estimate microzooplankton grazing. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser.. 51:221–227.

Sakamoto, S., Lim, W. A., Lu, D., Dai, X., Orlova, T. & Iwataki, M. 2021. Harmful algal blooms and associated fisheries damage in East Asia: current status and trends in China, Japan, Korea and Russia. Harmful Algae. 102:101787 pp.

Selosse, M. -A., Charpin, M. & Not, F. 2017. Mixotrophy everywhere on land and in water: the grand écart hypothesis. Ecol. Lett.. 20:246–263.

Shen, A., Xing, X. & Li, D. 2015. Allelopathic effects of Prorocentrum donghaiense and Karenia mikimotoi on each other under different temperature. Thalassas. 31:33–49.

Siswanto, E., Ishizaka, J., Tripathy, S. C. & Miyamura, K. 2013. Detection of harmful algal blooms of Karenia mikimotoi using MODIS measurements: a case study of Seto-Inland Sea, Japan. Remote Sens. Environ.. 129:185–196.

Skovgaard, A. 1998. Role of chloroplast retention in a marine dinoflagellate. Aquat. Microb. Ecol.. 15:293–301.

Steidinger, K. A. 2009. Historical perspective on Karenia brevis red tide research in the Gulf of Mexico. Harmful Algae. 8:549–561.

Stoecker, D. K., Hansen, P. J., Caron, D. A. & Mitra, A. 2017. Mixotrophy in the marine plankton. Annu. Rev. Mar. Sci.. 9:311–335.

Stoecker, D. K., Li, A., Coats, D. W., Gustafson, D. E. & Nannen, M. K. 1997. Mixotrophy in the dinoflagellate Prorocentrum minimum

. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser.. 152:1–12.

Takahashi, K., Benico, G., Lum, W. M. & Iwataki, M. 2019.

Gertia stigmatica gen. et sp. nov. (Kareniaceae, Dinophyceae), a new marine unarmored dinoflagellate possessing the peridinin-type chloroplast with an eyespot. Protist. 170:125680 pp.

Tamura, K., Dudley, J., Nei, M. & Kumar, S. 2007. MEGA4: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis (MEGA) software 4. 0. Mol. Biol. Evol.. 24:1596–1599.

Uchida, T., Toda, S., Matsuyama, Y., Yamaguchi, M., Kotani, Y. & Honjo, T. 1999. Interactions between the red tide dinoflagellates Heterocapsa circularisquama and Gymnodinium mikimotoi in laboratory culture. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol.. 241:285–299.

Van Dolah, F. M., Lidie, K. B., Monroe, E. A., Bhattacharya, D., Campbell, L., Doucette, G. J. & Kamykowski, D. 2009. The Florida red tide dinoflagellate Karenia brevis: new insights into cellular and molecular processes underlying bloom dynamics. Harmful Algae. 8:562–572.

Yñiguez, A. T., Lim, P. T., Leaw, C. P., Jipanin, S. J., Iwataki, M., Benico, G. & Azanza, R. V. 2021. Over 30 years of HABs in the Philippines and Malaysia: what have we learned? Harmful Algae. 102:101776 pp.

Yoo, Y. D., Jeong, H. J., Kang, N. S., Song, J. Y., Kim, K. Y., Lee, G. & Kim, J. 2010. Feeding by the newly described mixotrophic dinoflagellate Paragymnodinium shiwhaense: feeding mechanism, prey species, and effect of prey concentration. J. Eukaryot. Microbiol.. 57:145–158.

Zhang, Q. -C., Wang, Y. -F., Song, M. -J., Wang, J. -X., Ji, N. -J., Liu, C., Kong, F -Z, Yan, T. & Yu, R. -C. 2022. First record of a Takayama bloom in Haizhou Bay in response to dissolved organic nitrogen and phosphorus. Mar. Pollut. Bull.. 178:113572 pp.

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||