Physiological effects of copper on the freshwater alga Closterium ehrenbergii Meneghini (Conjugatophyceae) and its potential use in toxicity assessments

Article information

Abstract

Although green algae of the genus Closterium are considered ideal models for testing toxicity in aquatic ecosystems, little data about the effects of toxicity on these algal species is currently available. Here, Closterium ehrenbergii was used to assess the acute toxicity of copper (Cu). The median effective concentration (EC50) of copper sulfate based on a dose response curve was 0.202 mg L−1, and reductions in photosynthetic efficiency (Fv/Fm ratio) of cells were observed in cultures exposed to Cu for 6 h, with efficiency significantly reduced after 48 h (p < 0.01). In addition, production of reactive oxygen species significantly increased over time (p < 0.01), leading to damage to intracellular organelles. Our results indicate that Cu induces oxidative stress in cellular metabolic processes and causes severe physiological damage within C. ehrenbergii cells, and even cell death; moreover, they clearly suggest that C. ehrenbergii represents a potentially powerful test model for use in aquatic toxicity assessments.

INTRODUCTION

Microalgae play key roles in the primary productivity and biochemical cycles of aquatic systems. They are sensitive indicators of environmental change, and thus they have often been used to evaluate the impacts of metals, herbicides, and other pollutants in freshwater ecosystems (Qian et al. 2008); their physiology may be affected even under conditions of “no observable effect concentration” of a pollutant. In addition, the use of algae in toxicity assays confers numerous advantages: they are, for instance, easy to culture, requiring simple inorganic culture media, and they exhibit a rapid rate of growth and generational turnover (Lewis 1995).

Several physiological parameters are used as endpoints in algae-based ecotoxicological assessments, such as cell growth rate, biovolume, antioxidant system response, pigment production, and photosynthetic rate, which are compared and contrasted between treated and non-treated cells. Cell number is typically used as an indicator of growth in toxicological studies (Franklin et al. 2002), and many environmental contaminants affect the size and morphology of the tested cells via induction of oxidative stress (Sabatini et al. 2009). Chlorophyll autofluorescence (CAF) is an effective method for analyzing in situ photosynthetic efficiency, as well as to measure photosynthetic response to various stresses (Schreiber et al. 1995). Previous studies have reported the inhibition of microalgal photosynthesis by a wide variety of contaminants, leading to reductions in chlorophyll a (Chl a) concentrations (Ferrat et al. 2003), but little is known about the characteristics of CAF. Moreover, studies have shown that biochemical parameters play important roles in antioxidant defense systems in algal cells, which are estimated via antioxidant enzymatic assays (i.e., catalase, peroxidase, and superoxide dismutase) (Manimaran et al. 2012), but direct information about the formation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in microalgae is scarce.

The unicellular green alga Closterium ehrenbergii is found in freshwater ecosystems worldwide (Ichimura and Kasai 1984). This species is crescent-shaped (long, curved, and tapered at both ends) and is typically much larger (~300 μm in length) than most other unicellular microalgae (Lee et al. 2015), making observation of morphological and cellular changes relatively easy. It has long been used in research on algal sexual reproduction and cell cycling (e.g., Fukumoto et al. 1997), due to these features. In addition, previous studies have shown that C. ehrenbergii is very sensitive to a wide range of surfactants (Kim et al. 1998), and thus, recently it has been employed in additional toxicity evaluations and bioassays to detect the deleterious effects of hazardous substances on aquatic systems (Juneau et al. 2003, Sathasivam et al. 2016). However, to the best of our knowledge, there is little toxicological data available regarding the effects of various pollutants on Closterium species, and sensitivity of the species has not yet been compared to that of other microalgae (e.g., Aulacoseira granulate, Chlorella vulgaris, and Chlamydomonas sp.) by employing typical environmental contaminants, like heavy metals and pesticides.

In the present study, we quantified the sub-lethal effects of exposure to a well-known pollutant (copper, Cu) on a variety of morphological and physiological parameters of a strain of the freshwater green alga C. ehrenbergii, focusing on chlorophyll fluorescence characteristics, photosynthetic efficiency, and ROS levels. We then investigated the potential of Korean C. ehrenbergii isolates as testing models for aquatic toxicity assessments via comparisons of the median effective concentrations (EC50) of the test chemical copper sulfate (CuSO4), which is widely used as a biocide for cleaning swimming pools, in aquaculture farms, and even for removing harmful algal blooms (Kim et al. 2007), despite evidence of contamination of aquatic ecosystems and possibly even drinking water.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Alga culture and median effective concentration (EC50)

Cells of Korean C. ehrenbergii (Ce-01; Environmental Bio Inc., Seoul, Korea) were cultured in C medium (Watanabe et al. 2000) under conditions of 20 ± 1°C ambient temperature, a 12 : 12 h light-dark cycle, and a photon flux density of ~65 μmol photons m−2 s−1.

The effects of Cu toxicity on C. ehrenbergii was assessed using CuSO4 at concentrations of 0.1, 0.5, 1.0, 2.5, and 5.0 mg L−1. CuSO4 was procured from a commercial source (cat. No. C1297; Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) and prepared for standard stock solutions; all dilutions were prepared from standard stock solutions and all exposures were repeated in triplicate. The percentile inhibition and 72 h median effective concentration (EC50-72h) were calculated following the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development testing guidelines (OECD 2006), with EC50-72h estimates derived from a sigmoidal dose–response curve and plotted using Origin v. 8.5 software (MicroCal Software Inc., Northampton, MA, USA).

Measurements of chlorophyll fluorescence

Photosynthetic efficiency (Fv/Fm) was measured using a Handy Plant Efficiency Analyser fluorometer (Hansatech Instruments Ltd., Norfolk, UK). To determine the photosynthetic parameters of C. ehrenbergii, 2 mL of each sample was collected using a specimen cup. The fluorescence parameters, minimal fluorescence in the dark-adapted state (Fo), maximal fluorescence in the dark-adapted state (Fm), and variable fluorescence (Fv; Fm - Fo), were measured at 0, 6, 24, and 48 h following exposure to Cu concentrations of 0.1, 0.2, 0.4, and 1.0 mg L−1. Values of Fv and maximal quantum efficiency of photosystem II (PSII) photochemistry (Fv/Fm) were then derived from Fo and Fm.

ROS measurement

Dihydroxyrhodamine 123 (DHR123-D1054; Sigma) staining was used to measure ROS production, as DHR123 emits a green fluorescence when oxidized by ROS (Qin et al. 2008). Cells were independently treated with 0.2 mg L−1 Cu, with incubation periods of 6, 24, and 48 h. C. ehrenbergii cells were stained via exposure to DHR123 at a final concentration of 20 μM for 1 h, then harvested by centrifugation and twice rinsed with fresh C medium. The cultures were then re-suspended in fresh C medium, and mounted onto a slide and sealed; culture slides were observed with a fluorescence microscope (Carl Zeiss Axioskop, Oberkochen, Germany) to determine the level of ROS production in the cells. ImageJ software (NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA) was used to quantify relative CAF and ROS levels from the fluorescent microscopic images.

Statistical analysis

All data presented are mean values of triplicates. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with post hoc Student’s Newmann-Keuls test using Graphpad InStat (Graphpad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA) was used for comparisons between treated and untreated cultures, and p < 0.05 was used to determine significant differences between means.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Chlorophyll pigments have often been used as indicators in the monitoring of environmental stressors of plants, including algae (Li et al. 2005). Exposure of Cu to C. ehrenbergii induced a wide range of responses, depending on the Cu concentration; whereas exposure of Cu for 6 h at the initial experimental concentrations (i.e., 0.1–1.0 mg L−1) had only slight effects on Chl a levels (Fig. 1A), and Chl a was significantly lower in cells exposed to relatively high concentrations of Cu (2.5 and 5.0 mg L−1) (p < 0.05). In addition, Chl a levels were markedly lower after exposed to Cu for 72 h, with reductions of 12.1, 91.3, 98.2, 98.1, and 98.9% at 0.1, 0.5, 1.0, 2.5, and 5.0 mg L−1 of Cu concentrations, respectively. Similar results were reported by Chen et al. (2012), who found that Chl a concentrations significantly decreased in green algae exposed to Cu, a trend that was associated with increasing Cu concentrations (from 2 to 10 μM). Likewise, exposure of Cu resulted in marked reductions in Chl a concentration in the dinoflagellate Cochlodinium polykrikoides, an effect that was also more pronounced at higher Cu concentrations (Ebenezer et al. 2014). Overall, these results clearly demonstrate that the Korean strain of C. ehrenbergii used in this study is considerably more sensitive to Cu than other microalgae that have been tested previously (Cairns et al. 1978, Viana and Rocha 2005, Ebenezer and Ki 2013, Ebenezer et al. 2014).

Effect of different doses of copper to Closterium ehrenbergii. (A) Variation in chlorophyll a (Chl a) levels after 6 and 72 h exposure. (B) A dose response curve after 72 h exposure. (C) Variation in photosynthetic efficiency (Fv/Fm ratio) after 6 and 48 h exposure. Significant differences as determined by Student’s Newmann-Keuls test are represented as *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 level. Error bars represent ±standard deviation (n = 3).

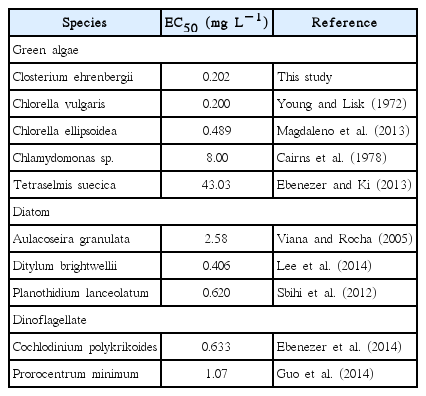

Estimations of EC50 values are useful for identifying environmental contaminants that may inhibit algal growth (Antón et al. 1993). The EC50 of Korean C. ehrenbergii after exposure to Cu for 72 h was calculated 0.202 mg L−1 (Fig. 1B). Previous studies have reported that EC50 for the green algae Chlorella ellipsoidea, Chlorella vulgaris, Chlamydomonas sp., and Tetraselmis suecica were 0.489, 0.200, 8.00, and 43.03 mg L−1, respectively (Young and Lisk 1972, Cairns et al. 1978, Ebenezer and Ki 2013, Magdaleno et al. 2013). In addition, EC50 for diatoms Planothidium lanceolatum, Ditylum brightwellii, dinoflagellates C. polykrikoides, and Prorocentrum minimum after exposure to Cu were reported 0.620, 0.406, 0.633, and 1.07 mg L−1, respectively (Sbihi et al. 2012, Ebenezer et al. 2014, Guo et al. 2014, Lee et al. 2014). Comparisons of available EC50 values indicated that species used in this study was generally more sensitive to Cu than other algae (Table 1), suggesting that it is a reliable model organism for aquatic toxicity assessments (Kim et al. 1998, Juneau et al. 2003, Sathasivam et al. 2016).

The median effective concentration (EC50) values of Closterium ehrenbergii and other microalgae after expose to copper

In addition, most pollutants including heavy metals inhibit PSII activity and interfere with photosynthetic reactions (Giardi et al. 2001). The Fv/Fm ratio is a useful and easily measurable parameter for the physiological state of the photosynthetic system in intact algae cells (Chen et al. 2012). To access the effects of Cu on the photosynthetic systems of C. ehrenbergii, we measured a range of parameters associated with photosynthetic processes. The fluorescence kinetic curves (both Fo and Fm) generated in the present study gradually decreased with increasing Cu concentrations and exposured time (data not shown). Fv/Fm of C. ehrenbergii was considerably affected by Cu toxicity and also declined with increasing Cu concentration and exposured time (Fig. 1C). Values of Fv/Fm slightly fell after exposure for 6 h (Fig. 1C) but significantly declined after exposure for 48 h at all concentrations of Cu, indicating that chlorophyll content and/or photosynthetic electron transport were inhibited by exposure to Cu. Similar responses have been observed in other algae exposed to various environmental pollutants, although the extent of inhibition varied among species; for example, Mamboya et al. (1999) reported that the photosynthetic efficiency of the brown alga Padina boergesenii significantly declined in response to increasing Cu concentration and exposured time. Moreover, in chlorophytes Chlorella vulgaris, Pseudokirchneriella subcapitata, dinoflagellates Cochlodinium polykrikoides, and P. minimum exposed to 3 μM, 250 μM, 1.0 mg L−1, and 0.5 mg L−1 of Cu, respectively, photosynthetic efficiency significantly declined in response to longer exposured times (Knauert and Knauer 2008, Guo et al. 2016a, 2016b). Such results not only demonstrate that exposure of Cu has an adverse effect on photosynthetic efficiency in many organisms, but also that the Korean C. ehrenbergii is a particularly sensitive to exposure of Cu (see Table 1).

Measurement of CAF is an efficient means of assessing physiological status in microalgae, which are capable of autofluorescence due to the presence of photosynthetic pigments (Trampe et al. 2011), as autofluorescence enables distinction between damaged and undamaged cells (Sato et al. 2004). As can be seen in Fig. 2A, relative CAF levels decreased with exposured time. In addition, ROS production for C. ehrenbergii was determined after exposure to 0.2 mg L−1 Cu for 6, 24, and 48 h (Fig. 2B); compared to controls, red fluorescence (autofluorescence) significantly decreased, whereas green fluorescence slowly increased with increasing exposured time, suggesting overproduction of ROS after exposure to Cu (Fig. 2A & B). The relative ROS level in C. ehrenbergii cells rose with increasing exposured time to Cu (Fig. 2B). Guo et al. (2014) reported that green fluorescence intensity significantly increased in the dinoflagellate P. minimum exposed to CuSO4 (p < 0.01), and gradually rose with increasing exposured time. In addition, Ishikawa et al. (1993) demonstrated that H2O2 is generated in chloroplasts and mitochondria, and immediately diffuses from these organelles to the cytosol. Algal cell toxicity can be promoted by the reaction of Cu (II) with H2O2, which further induces oxidative damage in algae cells (Chen et al. 2012). Moreover, we also observed changes in cell size and morphology, fragmentation of intracellular chloroplast in some algal cells, and loss of some cell contents (i.e., pigments) (Fig. 2C); these observations are consistent with the harmful effects described above.

Relative chlorophyll autofluorescence (CAF) levels (A) and reactive oxygen species (ROS) production (B) of Closterium ehrenbergii after expose to 0.2 mg L−1 copper at different intervals (6, 24, and 48 h). (C) Morphological changes of Closterium ehrenbergii after 6 and 48 h exposure to 0.2 and 0.4 mg L−1 of copper as seen by light microscope. Arrows represent chloroplast damage or loss of pigment. Significant differences as determined by Student’s Newmann-Keuls test are represented as *p < 0.01 level. Error bars represent ±standard deviation (n = 10). Scale bars represent: A & B, 50 μm.

According to United States Environmental Protection Agency guidelines, the general standard for maximum discharge of Cu into the environment is 3.0 mg L−1 (U.S. EPA 1986); however, we found that growth rates, Chl a levels, and photosynthetic efficiency were reduced, and ROS production enhanced for C. ehrenbergii exposed to levels of Cu as low as 1.0 mg L−1, with effects intensifying with increasing Cu concentrations. In a previous study, Sathasivam et al. (2016) demonstrated that growth rates, cell division, pigment levels, and CAF intensity decreased for Korean C. ehrenbergii exposed to NaOCl, whereas production of antioxidant enzymes increased, even at relatively lower contaminant concentrations. Moreover, expression of many stress-related genes (i.e., heat shock proteins, superoxide dismutase, glutathione S-transferase) increased for C. ehrenbergii exposed to Cu and other environmental pollutants (unpublished data). It is clear that C. ehrenbergii is extremely sensitive to a variety of environmental contaminants, and that the discharge limit for Cu concentrations established by the U. S. EPA is not low enough to avoid damage to the green alga C. ehrenbergii and possibly to other microalgae in environments.

CONCLUSION

The Korean freshwater green alga C. ehrenbergii exhibited a dose-dependent response when exposed to a typical pollutant copper. Comparisons of C. ehrenbergii’s EC50 values (0.202 mg L−1) to those of other organisms clearly demonstrated this species extreme sensitivity to Cu exposure. In addition, exposure to 1.0 mg L−1 of Cu significantly inhibits production of Chl a, reduces photosynthetic efficiency, and induces the generation of intracellular ROS, which may disrupt cell membrane functioning to cell death. General discharge standards of Korea limit Cu concentrations to 3.0 mg L−1, and thus this level may be high enough to potentially cause severe harmful to C. ehrenbergii and other aquatic organisms. From these results, we can conclude that the Korean C. ehrenbergii strain represents a useful model organism for aquatic toxicity assessments, and as such can provide a wealth of information pertinent to general risk assessments.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Drs. R. Guo and V. Evenezer for culture and experimental assistants. This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea Grant funded by the Korean Government (2015M1A5A1041805 and 2016R1D1A1A09920198).