Kelps in Korea: from population structure to aquaculture to potential carbon sequestration

Article information

Abstract

Korea is one of the most advanced countries in kelp aquaculture. The brown algae, Undaria pinnatifida and Saccharina japonica are major aquaculture species and have been principally utilized for human food and abalone feed in Korea. This review discusses the diversity, population structure and genomics of kelps. In addition, we have introduced new cultivar development efforts considering climate change, and potential carbon sequestration of kelp aquaculture in Korea. U. pinnatifida showed high diversity within the natural populations but reduced genetic diversity in cultivars. However, very few studies of S. japonica have been conducted in terms of population structure. Since studies on cultivar development began in early 2000s, five U. pinnatifida and one S. japonica varieties have been registered to the International Union for the Protection of New Varieties of Plants (UPOV). To meet the demands for seaweed biomass in various industries, more cultivars should be developed with specific traits to meet application demands. Additionally, cultivation technologies should be diversified, such as integrated multi-trophic aquaculture (IMTA) and offshore aquaculture, to achieve environmental and economic sustainability. These kelps are anticipated to be important sources of blue carbon in Korea.

INTRODUCTION

Global aquaculture production of seaweeds is approximately 34.7 million tons with an economic value of US$14.8 × 109 in 2019 (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations [FAO] 2021). Kelps in the order Laminariales accounted for approximately 47% of the total production with an economic value of US$7.7 × 109 (FAO 2021). Korea is one of the most advanced countries in seaweed aquaculture. The impetus for seaweed industry growth in Korea stems from a combination of a national wide support for seaweed cultivation and significant investment by the industry. Although Korea has an abundant and diverse seaweed flora, only three genera, Saccharina, Undaria, and Neopyropia / Pyropia represent 96% of the entire seaweed production of the country (FAO 2021). While the biomass of Neopyropia / Pyropia is mostly used for human consumption, kelps (Saccharina and Undaria) have been used for both human food and animal feed (Hwang and Park 2020, Park et al. 2021b). The production of Undaria pinnatifida and Saccharina japonica has increased due to, at least in part, high demand for abalone feeds in Korea (Hwang et al. 2012, 2020). Over 60% of total production of U. pinnatifida and S. japonica is used in the abalone industry.

Recently, applications of the harvested seaweed have been diversified for bioenergy, food ingredients, health and medical supplements, beauty products, etc. (Buschmann et al. 2017, Buschmann and Camus 2019). In addition, an increased demand for natural foods, containing beneficial bioactive compounds and produced from environmentally friendly farming practices, is expected to contribute more to the expansion of the seaweed industry (Jesumani et al. 2019 and references therein). To meet the demands in these industries in terms of productivity and quality of seaweed, diversification of species, cultivars (varieties) and cultivation technologies are required (Kim et al. 2017, Hwang et al. 2020).

The kelp aquaculture in Korea as well as in other countries has faced several challenges due to increasing anthropogenic impacts and climate change (Hwang et al. 2018, Kim et al. 2019, Hu et al. 2021). Recently, Hu et al. (2021) summarized the urgent challenges in the kelp aquaculture industry in China, including declining germplasm diversity, degradation of agronomic traits, genetic contamination between farmed and wild populations, the presence of polluted environments, ocean warming and ocean acidification. They also proposed effective solutions for the Chinese kelp aquaculture industry, including kelp germplasm preservation, site selection for phyconomic activities, kelp-based polyculture, and developing stressor-resistant cultivars. Korean kelp aquaculture industry is also experiencing similar challenges and has put investments to overcome these challenges. A few recent review articles discussed some of these issues in Korea, but they have mostly focused on breeding and cultivation technologies (e.g., Kim et al. 2017, Hwang et al. 2019, Hwang and Park 2020). In this review, we will discuss the biodiversity, population structure, and genomics of kelps in Korea. In addition, we will introduce new cultivar developments in Korea aquaculture considering climate change, and potential carbon sequestration.

DIVERSITY OF KELP IN KOREA

Brown seaweed of the order Laminariales are large macroscopic algae inhabiting the temperate coastlines worldwide, commonly referred as “kelps” (Lüning 1990, Bolton 2010, Kawai et al. 2016, Bringloe et al. 2020). They are recognized for their high productivity, ecological importance and for habitat structure. To date, there are 120 kelp species distributed in nine kelp families: Alariaceae, Agaraceae, Akkesiphycaceae, Arthrothamnaceae, Aureophycaceae, Chordaceae, Laminariaceae, Lessoniaceae, and Pseudochordaceae. Phylogenetic relationships between these families have been the subject of substantial revision (Boo et al. 1999, Lane et al. 2006, Kawai et al. 2013, 2017), but there is now a consensus with the analysis of multigene concatenation datasets (Jackson et al. 2017, Starko et al. 2019) (Fig. 1A). Historical biogeography analysis revealed that the kelps are most likely originated from the North Pacific, but it remains uncertain on which side of the oceanic basin (Starko et al. 2019). This explains the largest species richness of the kelps in this region and specifically on the coastlines of Korea, Japan, and Russia (Klochkova et al. 2018, Klimova and Klochkova 2021). In Korea, 10 kelp species have been reported belonging to five genera (Fig. 1A). These species include Agarum clathratum, Costaria costata, Ecklonia (E. bicyclis, E. cava, E. stolonifera, and E. kurome), Saccharina (S. japonica and S. sculpera), and Undaria (U. peterseniana and U. pinnatifida). With the exception of U. pinnatifida and S. japonica, the distributions of these species are unequal and regional. Notably, Ecklonia bicyclis (= Eisenia bicyclis) appears to be restricted to the Ulleung Island and S. sculpera (= Kjellmaniella crassifolia) has been found only in the Gangwon Province and might be on the verge of extinction in Korea (Fig. 1B).

The diversity of kelp of Korea. (A) Schematic phylogenetic tree of the kelps (Phaeophyceae, Laminariales) adapted from Stark et al. (2019). Kelp species found in Korea are indicated in bold with corresponding images of Undaria pinnatifida, Costaria costata, Ecklonia bicyclis, Ecklonia cava, Ecklonia stolonifera, Saccharina japonica, Saccharina japonica Sugwawon No. 203 strain, Saccharina sculpera. (B) Distribution of the 10 kelp species found on the coastlines of Korea.

The rich diversity of the kelps in Korea is extremely advantageous for the mariculture industry. The two major cultivated in Korea are kelp species U. pinnatifida and S. japonica. Some other kelp species have also been cultivated to provide biomass for the kelp forest restoration efforts (Kim et al. 2013). These species include the perennial Ecklonia bicyclis (formerly known as Eisenia bicyclis), E. cava, and E. stolonifera. Finally, attempts at cultivating S. sculpera are in progress (Yoo et al. 2018). If the restoration efforts of S. sculpera are successful, this endangered species could be brought back from being on the verge of extinction.

GENETIC MARKERS FOR KELP PHYLOGENY

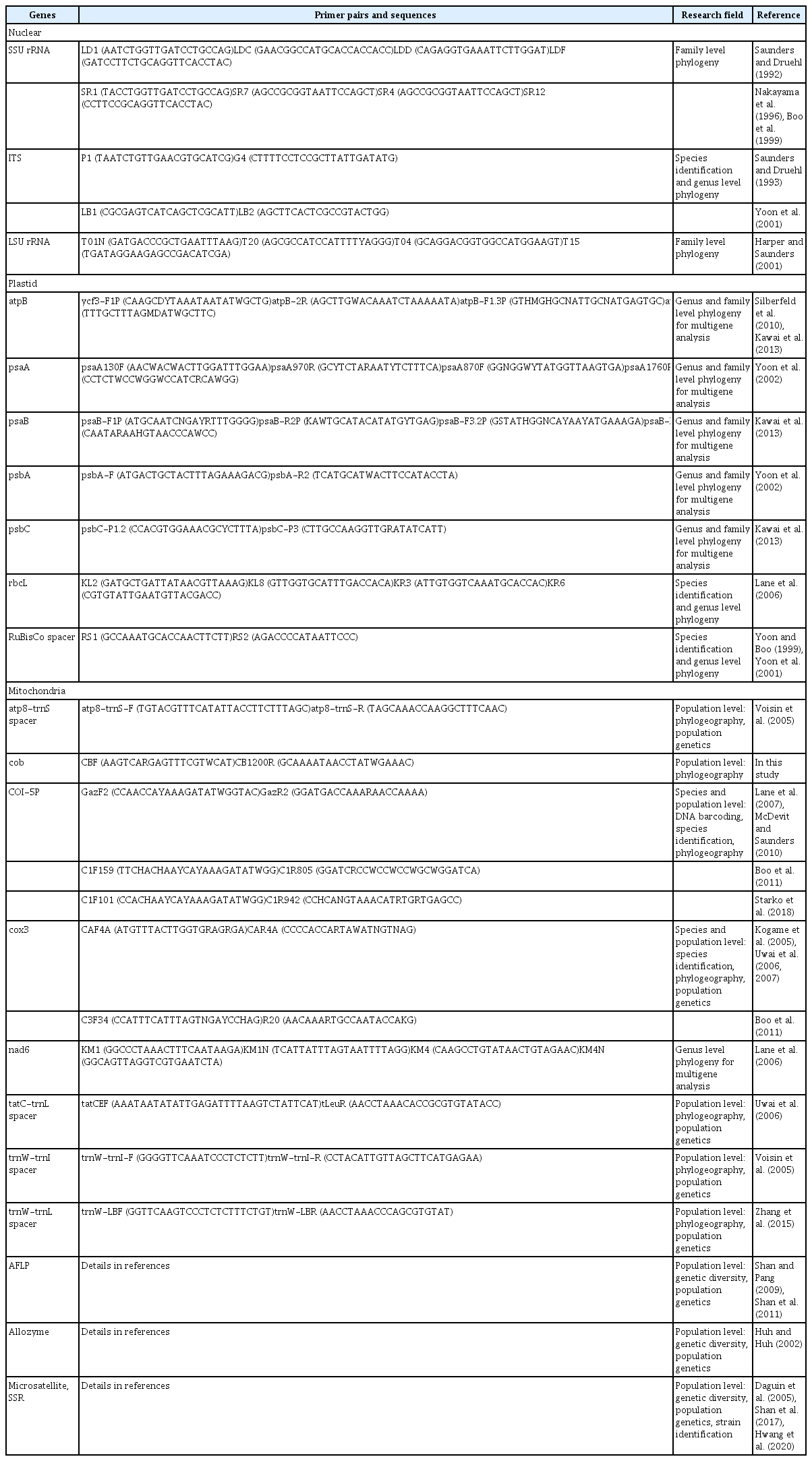

Genetic markers (see Table 1) have greatly enhanced our understanding of species identification and phylogenetic relationships of kelp (Saunders and Druehl 1992, Yoon et al. 2001, Lane et al. 2006, Starko et al. 2019). Nuclear markers such as small subunit ribosomal RNA (SSU) and internal transcribed spacer (ITS) were first used for the phylogeny of the Laminariales (Saunders and Druehl 1993, Boo et al. 1999). Yoon et al. (2001) analyzed two markers, plastid RuBisCo spacer and ITS region, to resolve phylogenetic relationships between the Alariaceae, Laminariaceae, and Lessoniaceae. They found eight clades instead of the traditional three families based on morphological characteristics (Setchell 1893, Setchell and Gardner 1925). They suggested the necessity of revised classification system based on new advances in DNA sequencing, additional markers are being developed for the further understanding of the phylogenetic relationships of kelps. Lane et al. (2006) used nuclear ITS, large subunit ribosomal RNA (LSU), plastid RuBisCo operon including ribulose-bisphosphate carboxylase large subunit (rbcL), RuBisCo spacer, ribulose-bisphosphate carboxylase small subunit (rbcS), and mitochondrial NADH dehydrogenase subunit (nad6). In this multigene analysis, they resurrected the genus Saccharina and proposed a new family, Costariaceae, which is now amended to be the Agaraceae (Kawai et al. 2017).

Genetic markers used for phylogenetic relationships, species identification, and population genetics of kelps

A DNA barcoding marker in mitochondria, the 5′ end of cytochrome-c oxidase subunit 1 (COI-5P), became a widely applied tool for the rapid identification of diverse eukaryotic species (Hebert et al. 2003). In the kelp, COI-5P and cytochrome-c oxidase subunit 3 (cox3) were used for species identification (Lane et al. 2007, Uwai et al. 2007, McDevit and Saunders 2010, Boo et al. 2011). Kawai et al. (2008, 2013) sequenced eight markers including plastid ATP synthase subunit beta (atpB), photosystem I P700 apoprotein A1 (psaA), photosystem I P700 apoprotein A2 (psaB), photosystem II protein D1 (psbA), photosystem II CP43 protein (psbC), rbcL, and mitochondrial cox1 and cox3 from representative kelps. Based on extensive molecular phylogenetic analysis, they suggested that Aureophycus aleuticus was basal to the derived kelps. Recently, Starko et al. (2019) analyzed mitochondrial and plastid genomes from diverse kelp species and reconstructed a comprehensive phylogeny using 120 genes from both organelle genomes and nuclear SSU and LSU rRNA. They suggested the northeast Pacific origin of complex kelps with a high resolution on deep nodes of kelp lineages.

POPULATION STRUCTURE OF SACCHARINA JAPONICA IN KOREA

Saccharina japonica is one of the most economically important kelp species in the Northwest Pacific. Since the first introduction from Hokkaido (Japan) to Dalian (China) during the 1920s, and following artificial cultivation in Shandong using floating rafts, comprehensive national wide cultivation efforts, and numerous culture strains were developed in China (Hu et al. 2021 and references therein). Thereafter, population studies of S. japonica have been reported, especially from China including natural populations from the Northwest Pacific. Shan et al. (2011) analyzed amplified fragment length polymorphism markers from six cultivars and six wild populations of S. japonica from China, Korea, and Russia. Zhang et al. (2015) used cox1 and trnW-trnL markers to explore phylogeographic patterns and genetic diversity of wild S. japonica populations in East Asia. Microsatellites revealed more detailed genetic differentiation even between populations (Li et al. 2016, Shan et al. 2017, Zhang et al. 2019). These molecular studies confirmed the introduction histories of S. japonica in China and Korea that originated from the Hokkaido populations.

On the other hand, Hokkaido strains were introduced in Korea in 1968 for aquaculture (Sohn 1998), but few population studies have been conducted using molecular tools. Recently, Hwang et al. (2020) distinguished genetic differences between cultivars from Korea (Sugwawon No. 301) and China (Huangguan No. 1) using simple sequence repeats (SSR) marker for the identification of S. japonica strains. They identified four SSR markers (i.e., SJ107, SJ42, SJ143, and SJ146) that clearly distinguished between two cultivars without intra-population variation. To develop genetic markers for interpopulation or inter-cultivar variation, further study is essential based on the recently published nuclear genomes of S. japonica (Ye et al. 2015, Liu et al. 2019).

POPULATION STRUCTURE OF UNDARIA PINNATIFIDA IN KOREA

The kelp U. pinnatifida is native to northeast of Asia (China, Japan, Korea, and Russia) but is now found in 14 other countries on five continents due to multiple human mediated introductions (Epstein and Smale 2017). Numerous genetic diversity and biogeographic studies were conducted for the introduced populations of U. pinnatifida and attempting at decipher introduction routes. Notably, the cox3 and three intergenic spacer regions, atp8-trnS, trnW-trnL, and tatC-trnL, were analyzed from native (i.e., Korea and Japan) and introduced populations (i.e., Europe and New Zealand) (Voisin et al. 2005, Uwai et al. 2006). Furthermore, the use of microsatellites also revealed high genetic diversities in both native and introduced populations (Daguin et al. 2005, Shan et al. 2012, 2019). However, the genetic diversity and biogeography within the native range remains largely unexplored. Huh and Huh (2002) investigated allozyme variation of wild and cultivated populations of U. pinnatifida from Korea and found high diversity within the natural populations, while the domestication (e.g., cultivar) appeared to have reduced genetic diversity. Similarly, Shan et al. (2018) used 30 microsatellites as genetic markers to hypothesize asymmetric gene flow between wild and cultivated Undaria populations.

Although population studies showed high genetic diversity within Undaria, limited taxon sampling may have hampered the study in reaching true diversity and a detailed population structure in Korea. To better understand the Undaria population structure, we collected 185 individuals of U. pinnatifida from 25 populations along the coast of Korea including 19 individuals of U. crenata (i.e., hybrid between U. pinnatifida and U. peterseniana, see below) from three locations (Fig. 2, Supplementary Table S1), using mitochondrial cox3 and cytochrome b (cob) markers (Table 1). We found a high haplotype (Hd = 0.735) but low nucleotide diversity (π = 0.00091) from Korean populations of U. pinnatifida. This result suggests that Korean U. pinnatifida may have experienced rapid population growth over a short period because sudden population expansion could not support the species to have sufficient time to accumulate enough mutations (Grant and Bowen 1998). The star-shaped topology of haplotype network supports a recent population expansion that many outlier haplotypes were derived from the two major haplotypes (C1 and C2 in Fig. 2B). The neutrality test (Tajima’s D = −2.19882, p < 0.01, Fu’s Fs = −39.567, p < 0.01) also supports a recent population expansion of Korean U. pinnatifida (Tajima 1989, Fu 1997).

Analysis of mtDNA (cox3 + cob) haplotypes of Undaria pinnatifida from Korea. (A) Geographic distribution of haplotypes from 25 populations with a representative specimens of U. pinnatifida. Pie chart denotes the proportion of haplotypes present in each population. (B) Statistical parsimony network of mtDNA haplotypes. Each circle denotes a single haplotype with size proportional to frequency. Small black dots represent missing haplotypes. Haplotypes are colored as shown in the key.

Two major haplotypes, differing by one mutation step, were found along the coasts of Korea, connected with many private haplotypes (Fig. 2). Haplotype C1 (C1-type) was found from Backryeongdo (west coast) to Goseong (east coast) with a wide gap in the southeastern coast. Haplotype C2 (C2-type) was found from the west to southeastern coast and Ulleungdo Island, but interestingly, it was absent above Pohang, which likely is the northern limit of the C2-type. In Pohang population, five haplotypes were identified. However, no major haplotypes were found, except for a single C1 haplotype. This suggests that, on the east coast, Pohang is a southern limit for C1-type, which likely migrated south via the North Korea Cold Current. It is also inferred to act as a geographical barrier for the C2-type. This is an interesting topic that warrants further study considering ecological and environmental factors in the region. Compared to the west and south coasts, the genetic diversity was higher in Jeju Island and the east coast with many private haplotypes. This result provides important information that wild populations of U. pinnatifida remain in those areas, and the populations should be protected from ocean warming. The expansion of cultivars of U. pinnatifida along the Korean coast may lead to a reduction in genetic variability.

In addition, U. crenata shares morphological characteristics between U. pinnatifida (i.e., sporophyll, midrib, and slightly pinnated blade) and U. peterseniana (gross morphology and sorus on blade). U. crenata is likely a hybrid between U. pinnatifida and U. peterseniana based upon morphology, however, in mitochondrial cox3 and cob sequence analysis, U. crenata was always nested within the U. pinnatifida clade, suggesting a natural hybrid. Sugwawon No. 203, the artificial hybrid strain between the female gametophyte of U. pinnatifida and the male gametophyte of U. peterseniana, shows similar morphological features with U. crenata. These results of molecular and morphological features strongly support the hybridization between two species, because only female gametophyte inherits mitochondria to the sporophyte of oogamous brown algae (Kimura et al. 2010, Choi et al. 2020).

GENOMICS

With the rapid growth of next generation sequencing technologies it has become possible to overcome the limitation of single markers of microsatellites cited above. Large-scale or genome-wide population genomic approaches, such as double-digest restriction site-association DNA sequencing (ddRAD-seq) or single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) detection using high-throughput sequencing are now available and have started to be employed to study kelps (e.g., Wood et al. 2020). In particular, two cultivated kelps have been extensively investigated using these methods: S. japonica (e.g., Shan et al. 2017, Zhang et al. 2019) and U. pinnatifida (e.g., Guzinski et al. 2018, Graf et al. 2021).

Using ddRAD-seq, Guzinski et al. (2018) genotyped 738 individuals for 14,622 SNP loci to study the populations of U. pinnatifida in Brittany, France. Their analyses revealed that genetic proprieties correlated with the type of habitat they considered (i.e., farms, marinas, and natural rocky reefs). Notably, the farms presented the lowest genetic diversity and levels of inbreeding, and the opposite was observed in marinas and natural populations. Furthermore, their analyses of the genetic structure of the population of U. pinnatifida in Brittany revealed that farms did not spill over to the wild but rather that leisure boating, and therefore marinas, contributed to the dispersal of U. pinnatifida. However, the analysis of ddRAD-seq can be limited by the absence of fully sequenced genome, notably to detect genome-wide patterns of evolution and adaptation.

These limitations were overcome with the sequencing of the nuclear genome of U. pinnatifida and the analysis of over 6.1 million SNP loci obtained from the re-sequencing of 41 individuals from Korea, France, and New Zealand (Graf et al. 2021). This study revealed that different type of human activities (i.e., cultivation and introduction) had different effects on the evolution of the genome of U. pinnatifida resulting in a different genomic landscape. The genomic landscape of the introduced populations (France and New Zealand) reflected founder effects, when a small number of individuals were introduced outside of the native range. In consequence, this resulted in a low genetic diversity, low recombination rates and high levels of homozygosity in the genomes of the introduced populations. On the other hand, the genome landscape of the Korean cultivated individuals was unexpectedly characterized by high genetic diversity, high recombination rates and low homozygosity. The cultivated population in France (Guzinski et al. 2018) and Korea (Graf et al. 2021) appeared to present opposed genetic proprieties and this was likely explained by the difference in scale of the cultivation. In France, the cultivation is very limited by local farmers whereas in Korea it is very large by numerous commercialized seedling providers; therefore, the methods employed in the Korean mariculture (i.e., fertilization in large indoor pool using sporophyll of multiple individuals) contributed to form the diverse genome landscape of the Korean cultivated individuals (Graf et al. 2021). The characteristics of genomic landscape observed in the Korean cultivated populations suggest that these populations could serve as reservoirs of evolutionary potential for conservation purposes. Conversely, the apparent genetic erosion in the U. pinnatifida cultivated in France could potentially represent a risk for the adaptation of cultivated individuals in face of global changes. It is important to notice that the individuals studied in Graf et al. (2021) were not filed or registered cultivars following the International Union for the Protection of New Varieties of Plants (UPOV)’s Aquatic Plant Variety Management System (APVC 2021) and that the genome landscape of the registered cultivars remains to be explored.

These recent progress in genomics, represent a foundation for future research. Notably, the connection of genetic and phenotypic information, through genome-wide association studies (GWAS) and / or quantitative trait locus mapping (QTL) will be necessary to fully elucidate the effect of cultivation on U. pinnatifida, but will also drive breeding programs. These types of programs necessitate important resources to genotype large number of individuals to identify SNPs linked to the phenotypic variation of interest (e.g., size of the sporophyte). To that end, the 6.1 million high-quality SNP dataset presented in Graf et al. (2021) served to design an extremely high throughput genotyping array containing 75K highly informative and genome-wide SNP loci for U. pinnatifida (Fig. 3A). The balance between the cost of sequencing and the depth of genotyping is excellent with the designed SNP microarrays. This powerful tool will serve to study the genome-wide evolution of U. pinnatifida in Korea and around the world, as well as links between genotypes and phenotypes. These studies will bring important insights for the conservation of the kelp forests in Korea and the development of new cultivars.

Toward the future of the research on Undaria pinnatifida. (A) Design protocol of the U. pinnatifida single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) microarray. The circus plot and maps are from Graf et al. (2021). (B) Principal Component Analysis of 75,180 variants loci called in 459 individuals of U. pinnatifida from various populations sampled around Korea. (C) Protocol example for quantitative trait locus mapping (QTL) and genome wide association (GWAS) analysis of cultivated U. pinnatifida.

Preliminary analysis of over 450 individuals from around 20 populations genotyped using the 75K SNP microarrays have proved its power in detecting informative loci among individuals of U. pinnatifida around the world. They have already started to reveal the structure of the population of U. pinnatifida in Korea with unprecedented resolution (Fig. 3B). Somewhat contrasting with the mitochondrial haplotype analysis (Fig. 2), it appears that the east coast represents a clearly segregated genetic cluster in Korea. On the other hand, the west and south coast share more genetic similarity, and the structure even did not correlate with the geographic distribution (Fig. 3B). Further analyses are needed to fully grasp the information contained in this early dataset of SNP, but it already offers promising and interesting results. Furthermore, in the future, SNP microarray chips will be used in different studies of U. pinnatifida and other economically and ecologically important kelp species. It will allow population genomics studies at unprecedented scale to deeply understand the dynamics of U. pinnatifida forests in Korea, but also enable the monitoring introductions around the world (Fig. 3). To that end, the SNP microarray can prove very useful, through the genetic assisted development of cultivars (e.g., Jiang 2015). The SNP microarray is being used in the GWAS and QTL analysis of valued phenotypes for the cultivation industry in the Sugwawon 204 and Sugwawon Cheonghae cultivar (Fig. 3C). This study aims at identifying crucial genome regions linked to important phenotypes for the mariculture. Establishing collection of gametophytes, genotyping them, identifying valuable crosses and finally produce lineages of sporophytes will be the next steps in the genetic assisted development of U. pinnatifida cultivars in Korea.

KELP AQUACULTURE IN KOREA

Undaria pinnatifida (Myeok in Korean) was first described in 1814 during Chosun Dynasty in a marine fisheries book called ‘Jasaneobo,’ written by Jeong Yakjeon. He described Myeok as sweet taste excellent food for postpartum women. Traditionally, Korean women eat Miyeok or ‘Miyuk’ seaweed soup for a few weeks after giving birth. The first artificial seeding of U. pinnatifida occurred in 1967 (Sohn 1996, 1998, Hwang and Park 2020). Since 1970s, the production of U. pinnatifida increased dramatically in nearshore shallow waters of Korea and is sometimes referred to as the “Black Revolution” of the aquaculture industry (Ha et al. 2018). Korea produced nearly 500,000 tons in 2019, which is 22% of global kelp production (FAO 2021).

Saccharina (Dashima in Korean) has traditionally been utilized as food and medicine over four-hundred years in Korea. Dashima was first described in 1611 during Chosun Dynasty in a review book on Korean foods, called ‘Domundaezak,’ written by Heo Gyun. The utilization of this alga for medicine was also described in 1610, in a book entitled ‘Donguibogam,’ the principles and practices of eastern medicine, written by Heo Jun. Aquaculture of S. japonica first occurred in 1968 when the Japanese variety of this alga was first introduced from Hokkaido, Japan (Chang and Geon 1970). Since then, selection and selective breeding have been actively undertaken (Hwang et al. 2017). The production of this alga has rapidly increased since 1974. Korea produced over 600,000 tons in 2019, which is about 5% of the global kelp production (FAO 2021).

CULTIVAR DEVELOPMENT VIA SELECTION AND BREEDING

Undaria pinnatifida cultivars development begun in 2006 in Korea. Three mature sporophytes were collected from natural habitats in Ulsan and Jeju, and from a seaweed farm in Wando, Jeonnam Province, Korea, respectively. The male and female gametophytes of these three strains were propagated in laboratory, and pure cell lines of them were selected after F4 generation was produced in 2011. Among them, Sugwawon cheonghae is the favored cultivar in Undaria farms in Jeonnam Province, Korea (Table 2, Fig. 4). Most cultivars with variety protection rights were developed by selection, but Sugwawon No. 202 was developed by hybridization between a female gametophyte of Sugwawon cheonghae and a male gametophyte of Sugwawon No. 201.

The breeding network of the kelp Undaria pinnatifida and Saccharina japonica showing various cultivars produced and used for cultivation in Korea. Solid box indicates registered cultivar and dotted box indicates under evaluation.

Considering climate change, it is critical to develop high-temperature resistant varieties of kelp species. The thermal tolerant cultivars are typically important in Korea because over 60% of kelp production are used for abalone feeds, and no live feeds are available for abalone during the late summer to fall. An interspecific hybridization between female U. pinnatifida collected from Wando and male U. peterseniana from Udo, Jeju Island was made in 2006 (Hwang et al. 2012, 2014). This hybrid (Sugwawon No. 203) has the blade length much greater than its parental plants and can grow even in June after U. pinnatifida stops its growth in April. It has the potential to provide biomass to abalone for a longer period of time. Sugwawon No. 203, however, has not been widely distributed due to the delay in maturation and difficulty in seeding the meiospores for cultivation in the following year.

The development of S. japonica cultivars was not as fast as that of U. pinnatifida in Korea. Jeongwan No. 1 was introduced from a kelp farm Fujian, China (presumably the Chinese cultivar, Huangguan No. 1) in 2009. This cultivar was highly productive in China but did not grow well in Korean water. The thalli were easily broken and / or detached from culture ropes (Hwang et al. 2018, 2020). The Sugwawon No. 301 was selected from late-grown fronds at Haenam, Jeonnam, Korea. This was the F3 generation of plants originally collected from a kelp farm at Wando, Jeonnam, in 2006 (Table 2, Fig. 4). Sugwawon No. 301 can grow during the summer months and showed an enhanced growth performance. Interestingly, this cultivar displayed different morphological traits, temperature tolerance, and resistance to wave action when they the cultivar grew in different environments (Hwang et al. 2017, 2018). Sugwawon No. 301 is currently under evaluation for variety protection. Korea joined in the UPOV in 2002 (Park et al. 2016, Hwang et al. 2019, 2020) and applied for the varieties protection system to seaweed since 2012. To date, six kelp cultivars, including five Undaria and one Saccharina varieties have been registered, and four varieties are currently under evaluation (Table 2, Fig. 4).

DIVERSIFICATION OF CULTIVATION TECHNOLOGY FOR SUSTAINABLE PRODUCTION OF KELPS

Intensive seaweed farms experience nutrient limitation during their growing season, causing discoloration and poor growth, resulting in low quality of products (Kim et al. 2017, Park et al. 2018). Therefore, it is critical to develop new approaches of cultivation to maintain a sustainable seaweed aquaculture industry. Integrated multi-trophic aquaculture (IMTA) has been suggested as a potential solution to resolve this issue. In Korea, most finfish and shellfish aquaculture occur in Gyeongnam Province, southeast of Korea, while most seaweed cultivation occurs in Jeonnam Province, southwest of the country, with very little overlap between fish and seaweed aquaculture areas. The areas near fish farms experience eutrophication and even harmful algal blooms while the intensive seaweed farms suffer with nutrient limitation (Park et al. 2018, 2021a). To achieve environmental and economic sustainability, IMTA practices were conducted co-cultivating kelps (U. pinnatifida and S. japonica), pacific oysters (Crassostrea gigas) and sea cucumbers (Stichopus japonicas) adjacent to finfish Sebastes schlegeli or red seabream (Pagrus major) cages. All organisms in this IMTA system grew equally well or better than those grown in monoculture farms (Park et al. 2018, 2021a). Seaweeds removed nitrogen very efficiently and tissue nitrogen content in the kelps was up to 3.5% in the IMTA system, which is much higher than that in monoculture (< 2.5%) (Park et al. 2021a, 2021b).

Offshore seaweed (mainly Saccharina latissima) aquaculture is being conducted in Europe (Germany, Belgium, the Netherlands, Norway) and in North America (Canada and the United States). In these countries, very little area in near shore environments are available due to a multitude of interests competing for space. To encourage the offshore aquaculture in Europe, the EU has supported projects for multi-use of offshore wind farms for aquaculture (Wever et al. 2015, van den Burg et al. 2016). For example, UNITED (multi-Use platforms and co-locatioN pilots boosting cost-effecTive, and Eco-friendly and sustainable production in marine environments) has supported pilot projects to develop multi-use platforms or co-location of different activities in a marine and ocean space for European maritime industry and local ecosystems. One of the attempts is to install seaweed farms near offshore wind turbines, attempting to automate the growth and harvest of kelps (https://cordis.europa.eu/project/id/862915). Recently, potential environmental risks and risk governance of seaweed cultivation at offshore wind farms were evaluated (van den Burg et al. 2020). They concluded that current risk governance for multi-use is poorly equipped to deal with the systemic nature of risk, suggesting a lot of challenges still remain for offshore seaweed cultivation.

Offshore seaweed (Macrocystis pyrifera) farming in the United States started in 1970s as part of Marine Biomass Program to produce biomass for biofuel (Neushul 1980, 1986, North et al. 1982). This program, however, was discontinued in 1986. The offshore seaweed aquaculture research and development has resumed more than 3 decades later, in 2018 with a support of the Advanced Research Projects Agency-Energy (ARPA-E) of the US Department of Energy. This program is called Macro Algae Research Inspiring Novel Energy Resources (MARINER), which is the largest funding opportunity for seaweed aquaculture in the United States. This program attempts to use over 11,350,000 km2 of the exclusive economic zone (EEZ) for seaweed (mostly kelps) cultivation. The EEZ may provide sufficient areas to produce large amount seaweeds with minimizing conflict with recreational, fishing, transportation and military activities (Kim et al. 2019).

In Korea, seaweed aquaculture occurs mostly in the nearshore environment. Most nearshore areas suitable for seaweed farming have been leased to the farmers and therefore, an expansion of seaweed cultivation will most likely have to move further offshore (Buck et al. 2004, Kim et al. 2019). There has been some effort for offshore seaweed aquaculture in Korea, including surveying environmental factors, designing farm structures and harvesting devices, etc. (Yoo et al. 2011, Choi 2020). There was even an attempt to grow kelps in the offshore environment, but it was not successful due to severe weather (i.e., storms) during the growing season. Although the EEZ should be used for sustainable seaweed aquaculture industry, there are many challenges and conflicts. For example, site selection for cultivation will be critical. Upwelling areas would be good to fuel the growth of seaweed, otherwise nutrients would be supplied by other sources (e.g., offshore finfish farm, slow-release fertilizers, etc.), which could prove prohibitively expensive and may even cause harmful algal blooms. Kelp species have been suggested as the most appropriate species for offshore cultivation in cool temperate waters due to their low requirement for maintenance and harvest in comparison to other aquaculture species (Kim et al. 2017). However, cultivar development will still be needed to improve both productivity and composition of the kelps in the offshore environment. Innovative cultivation and harvest systems will need to be developed, which may include free-floating farm systems, pumping deep seawater to supply nutrients to the kelp, autonomous diving systems to protect farms from wave motion, automated monitoring systems, drone technology to move farm systems to safe locations during storm events and for harvest, etc. (Kim et al. 2017, 2019).

KELP AQUACULTURE FOR CLIMATE CHANGE ADAPTATION

Blue carbon has received a global attention and considered as a potential solution to achieve the targets of the Paris Agreement, which is to limit global warming to 1.5°C compared to pre-industrial levels (Yong et al. 2022). Among blue carbon sources, seaweed has recently received a newest interest as a biological ocean-based carbon dioxide removal (CDR). Korea, in fact, is one of the first countries evaluating potential carbon reduction by seaweed. The project entitled “greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions reduction using seaweeds” began in 2006 and developed baseline and monitoring methodologies for the Clean Development Mechanism (CDM) and Project Design Document (PDD) of the Kyoto Protocol (Chung 2007, Chung et al. 2011). In addition, Korea Fisheries Resources Agency (FIRA) has conducted marine forests restoration projects for more than two decades. Over 20,000 ha of seaweed forest had been restored nationwide by 2020. These restored seaweed forests are currently being evaluated for carbon sequestration potential (FIRA 2021). A recent study even estimated specific CDR by S. japonica and U. pinnatifida aquaculture. The amount of CDR was over 50,000 tons per year, equivalent to nearly 2% of CO2 discharged from all wastewater treatment plants in Korea (Park et al. 2021a). The major challenge, however, is that the majority of seaweed production is decomposed into the ocean within a relatively short time (weeks to years). Seaweed, therefore, is not considered as a net carbon sink. However, recent studies have suggested potential contribution of seaweed to climate change mitigation strategies (Krause-Jensen and Duarte 2016, Duarte et al. 2017, Wu et al. 2022). For example, Oceans 2050 project led by Carlos M. Duarte and colleagues is evaluating sediment containing organic carbon originated from seaweed farms. Twenty one seaweed farms in 13 countries on 5 continents are participating in this project including 3 kelp farms in Korea (https://www.oceans2050.com/seaweed).

Offshore seaweed aquaculture can be another possibility for ocean-based CDR (see above for more details about offshore seaweed aquaculture). Wu et al. (2022) estimated offshore seaweed aquaculture for carbon sink. They suggested that mature seaweed from the farms will rapidly sink to the seafloor and unload the biomass there. The sunken biomass will then remain at the sea floor for centuries to millennia, achieving a carbon sink. Recent studies suggest that over 44% of seaweed production are exported from the coastal habitat, and approximately 25% of the exported organic carbon by seaweed are sequestered in long-term reservoirs, such as coastal sediments and the deep sea (Krause-Jensen and Duarte 2016, Ortega et al. 2019). The Ocean Panel (The High-Level Panel for a Sustainable Ocean Economy) estimated that seaweed farming may absorb 50–290 million tons of CO2 eq per year (Hoegh-Guldberg 2019). However, the margin of error for this estimate is huge, and therefore, most of the ideas for seaweed-based CDR should be thoroughly tested. Most effort on CDR by seaweed (offshore) aquaculture has been made in the Europe and the United States. As mentioned above, cultivar development, and innovative cultivation and harvest technologies are essential for offshore seaweed aquaculture. These countries still need to develop cultivars of their native species and cultivation technologies suitable for their coastal waters. To test seaweed-based CDR ideas in Asian waters, it is critical for these countries to actively participate in these global efforts using their germplasm to help reach the global goal of net-zero carbon dioxide emission by 2050 (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change 2021).

CONCLUSIONS

The kelps, U. pinnatifida and S. japonica are dominant aquaculture species in Korea and have been utilized for human food and abalone feed. These seaweeds also provide important ecosystem services role in the natural habitats in Korea. S. japonica occurs throughout the coasts of Korea; however, interpopulation or inter-cultivar variation needs to be studied in this alga. Although the aquaculture of the kelps started in 1960s, cultivar development only begun in early 2000s for both species in Korea. To date, five U. pinnatifida and one S. japonica varieties have been registered to the UPOV. Four varieties are currently under evaluation. However, there is still a need to put more effort developing high-temperature resistant varieties of kelp species considering climate change and the rapid expansion of abalone industry. Molecular techniques should be used to accelerate the process of cultivar development. To meet the demands for seaweed biomass in various industries while achieving environmental and economic sustainability, new approaches for cultivation will be required (e.g., IMTA and offshore seaweed aquaculture). However, there are challenges for these approaches to overcome, e.g., site selection, development of cultivars, cultivation and harvest technologies, reduction in stakeholder conflicts, etc. The kelp has also received much attention as a source of blue carbon. Korea needs to participate in these global efforts more actively to develop new sources of carbon sinks, and to help achieve its emission reduction goal of 40% by 2030 as well as the global goal of net-zero carbon dioxide emission by 2050. Recently, Hu et al. (2021) proposed an ‘East Asian Kelp Consortium (EAKC)’ to develop a broad platform for official, enhanced and supported scientific cooperation, to enhance the management and preservation of both wild and farmed kelp resources in East Asia. This is a valuable suggestion. It is important for scientists, government agencies, and entrepreneur in the fields of kelp aquaculture, ecology, taxonomy, and genomics from Korea (South and North), China, and Japan to join in a consortium to help efficiently preserve and wisely utilize the important kelp resources in the region.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

Supplementary Table S1. Collection information, haplotype codes, and GenBank accession numbers of specimens used in this study (https://www.e-algae.org).

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research was supported by grants from the National Institute of Fisheries Science, Republic of Korea (R2022012) to EK Hwang, the Korea Institute of Marine Science and Technology Promotion (KIMST) funded by the Ministry of Oceans and Fisheries (MOF) (20180430, 20210469) to HS Yoon and the Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education (NRF-2017R1A6A1A06015181) to JK Kim.

Notes

The authors declare that they have no potential conflicts of interest.