Recent advances in seaweed seedling production: a review of eucheumatoids and other valuable seaweeds

Article information

Abstract

Modern seaweed farming relies heavily on seedlings from natural beds or vegetative cuttings from previous harvests. However, this farming method has some disadvantages, such as physiological variation in the seed stock and decreased genetic variability, which reduces the growth rate, carrageenan yield, and gel strength of the seaweeds. A new method of seedling production that is sustainable, scalable, and produces a large number of high-quality plantlets is needed to support the seaweed farming industry. Recent use of tissue culture and micropropagation techniques in eucheumatoid seaweed production has yielded promising results in increasing seed supply and growing uniform seedlings in large numbers in a shorter time. Several seaweed species have been successfully cultured and regenerated into new plantlets in laboratories using direct regeneration, callus culture, and protoplast culture. The use of biostimulants and plant growth regulators in culture media increases the seedling quality even further. Seedlings produced by micropropagation grew faster and had better biochemical properties than conventionally cultivated seedlings. Before being transferred to a land-based grow-out system or ocean nets for farming, tissue-cultured seedlings were recommended to undergo an acclimatization process to increase their survival rate. Regular monitoring is needed to prevent disease and pest infestations and grazing by herbivorous fish and turtles during the farming process. The current review discusses recent techniques for producing eucheumatoid and other valuable seaweed farming materials, emphasizing the efficiency of micropropagation and the transition from laboratory culture to cultivation in land-based or open-sea grow-out systems to elucidate optimal conditions for sustainable seaweed production.

INTRODUCTION

Natural seaweeds are macroalgae that thrive on solid bottom substrates such as rocks, dead corals, pebbles, shells, and other plant materials. The three major groups of macroalgae are green algae (Chlorophyceae), brown algae (Phaeophyceae), and red algae (Rhodophyceae). The use of seaweed in human civilization can be traced back to the Neolithic period, with the discovery of seaweed species remnants at the Monte Verde archaeological site in southern Chile (Erlandson et al. 2015). The discovery provided the most definitive evidence of prehistoric human-seaweed interactions, demonstrating that humans gathered and consumed seaweeds for medicine or food at least 14,500 calendar years ago (Dillehay et al. 2008).

Current seaweed farming practices, particularly eucheumatoid cultivation in Southeast Asia, rely considerably on seed stock collected from natural beds. This method, however, has some disadvantages, such as physiological variation in the seed stock and over-exploitation of the donor population (Kim et al. 2017). Another alternative method is to use vegetative cuttings from previous harvests as the seed materials. Despite this, the repeated clonal propagation reduces genetic variability, resulting in a lower growth rate, carrageenan yield, and gel strength (Sulistiani et al. 2012). Also, as genetic variability decreases, seaweed vulnerability to diseases increases, potentially leading to seedling shortages and posing a threat to the seaweed farming industry. To overcome these limitations, scientists attempted to propagate and produce seaweed seedlings in the laboratory using tissue culture and micropropagation techniques, followed by hatchery and sea-based grow-out. Micropropagation allows for the rapid production of a large number of individuals in a short amount of time, which can then be used as seedlings for land-based cultivation or sea-based farming (Yong et al. 2014b). Hurtado and Biter (2007) demonstrated that this method has a high potential for providing seedstock for commercial eucheumatoid seaweed farming in a study in which they used tissue culture to induce callus formation in Kappaphycus alvarezii var. adik-adik, and then used the regenerated plantlets as propagules for further growth in a land-based nursery, and then as seedlings for seaweed farming. This approach will not only aid in the conservation of the wild marine algae population, but it will also allow for sustainable seaweed production for commercial purposes.

Over the last decade, numerous studies on the use of micropropagated seedlings for seaweed cultivation have been published, with many of them emphasizing the importance of cultivating high-quality seedlings as a critical factor in increased seaweed production capacity (Reddy et al. 2017, Rama et al. 2018, Budiyanto et al. 2019, Cahyani et al. 2020). Tissue culture has been identified as one of the methods for improving seaweed seed quality, producing high-quality seedlings with a faster growth rate than conventionally propagated seedlings (Yong et al. 2014a, 2015a, Budiyanto et al. 2019). However, most studies focused on improving micropropagation procedures or enhancing farming practices (Baweja et al. 2009, Buschmann et al. 2017, Kim et al. 2017, García-Poza et al. 2020), with little attention paid to the transition from laboratory cultivation to sea-based farming, which is an essential link between high-quality farming material production and long-term farming sustainability. This review examines recent advances in seaweed seedling production and cultivation strategies, emphasizing techniques developed for eucheumatoids (Fig. 1) or other related seaweed species that could potentially be applied to eucheumatoids. The study also integrates the two vital elements of laboratory seedling production and sea-based grow-out to address the rising seedling shortage problem in the global seaweed farming industry.

Advances in eucheumatoid seaweed propagation and cultivation techniques: callus induction (A), direct regeneration (B), micropropagation (C), flask culture (D), tank culture (E), indoor culture / farming (F), nursery tank-based culture (G), outdoor acclimatization (H), hatchery tank-based grow-out (I), sea-based grow-out (J), sea-based farming (K), and final seaweed harvest (L).

CONVENTIONAL SEAWEED SEEDLING PRODUCTION

The two primary forms of seedlings (propagules) used in traditional seaweed farming were vegetative fragments and reproductive cells (spores or gametes) (Carl et al. 2014, Radulovich et al. 2015). Vegetative fragments have been used to successfully propagate certain seaweed species with higher proliferation potential, such as the Kappaphycus, Gracilaria, Gelidiella, Gelidium, and others (Mantri et al. 2017b, García-Poza et al. 2020). However, there are several drawbacks to this propagation method, one of which is that a quarter of the total harvested crop is used as seed materials for the subsequent farming process (Radulovich et al. 2015). Following that, using seedlings from the same genotype repeatedly causes vigor loss, reduced production capacity, and increased susceptibility to diseases and pests (Yong et al. 2014a, Buschmann et al. 2017).

Meanwhile, reproductive cells (spores or gametes) have been used to propagate species with high reproductive potentials, such as the Pyropia, Ulva, Saccharina, Undaria, and others (Blouin et al. 2011, Carl et al. 2016, Peteiro et al. 2016). Spores are typically cultured on an artificial substrate and maintained in a land-based seedling rearing facility until they reach the appropriate plantlet size for transplantation. Following that, the plantlets are attached to ropes and released into the open sea to be used in field cultivation (Hafting et al. 2015, Camus et al. 2016). This method can provide a reliable supply of seedlings for seaweed farming. Still, its efficacy is largely determined by the reproductive ability of the seaweed species (Gupta et al. 2018). Researchers may develop a combination of various abiotic factors to induce reproductive maturity and eventual sporulation independent of the natural life cycle based on their understanding of seaweed reproductive biology (Carl et al. 2014, 2016). However, rigorous, long-term experimentation is needed to optimize the conditions that can trigger maturity and sporulation in a given species (Gupta et al. 2018). Furthermore, since this optimum condition is particular to a particular species and varies with plant age and physiological background, it is unlikely to be reproducible in all circumstances (Carl et al. 2014).

Conchocelis culture has also been reported to have the potential to revolutionize seedling production and farming of Pyropia species (Zhong et al. 2016). Conchocelis development involves three major phases: vegetative growth, conchosporangia production, and conchospore release, all of which are influenced by environmental conditions (Wang et al. 2008). Although the discharged conchospore will eventually develop into a full thallus, this approach faces the same limitation as the one described above in that it is species-specific. In China, seedling production of Pyropia dentata is impeded by low seedling efficiency of the species as a result of trials using the conchocelis method, which was adopted for Pyropia yezoensis and Pyropia haitanensis, but no conchosporangia were successfully produced (Zhong et al. 2016). Thus, for industrial seedling production, it is critical to use optimum culture conditions to manage the development and reproduction of species-specific conchocelis cultures. Besides, sporelings derived from released tetraspores were successfully demonstrated for mass propagation of the male gametophyte of Palmaria palmata in tank cultures (Schmedes et al. 2019). However, environmental cues that induce fertility and spore / gamete release in the species are difficult to detect, necessitating a fundamental understanding of the underlying biological mechanisms to control the rate of embryo formation and reproductive cycles for successful cultivation (Charrier et al. 2017). Indeed, an alternative seedling production system that does not rely on vegetative fragments or reproductive cells is expected to address all of these issues.

TYPES OF SEAWEED TISSUE CULTURE

Chen and Taylor initiated seaweed tissue culture by establishing the totipotency of red algae using medullary tissue explants from female gametophytic fronds of Chondrus crispus Stackhouse, with considerable interest in improving the overall economic prospects of seaweed resources (Chen and Taylor 1978). Following that, tissue culture and micropropagation allowed for mass production of various seaweed species, providing seedling stock for cultivation and ensuring a consistent supply of certain seaweed strains with desirable traits (Reddy et al. 2008b). The general methods used in seaweed tissue culture include direct regeneration, callus culture, and protoplast culture. This section will further discuss the current status of these three critical types of seaweed tissue culture.

Direct regeneration

Direct regeneration is preferred for growing true-to-type plantlets because it has a lower somaclonal variation rate than callus culture (Yong et al. 2014b). This type of tissue culture is suitable for the clonal propagation of seaweeds. It allows a large number of identical seedlings to be produced for cultivation. The formation of adventitious branches from explants has been well established in the Gracilariales, Gelidiales, Halymeniales, Ceramiales, and Gigartinales (Reddy et al. 2008b, Baweja et al. 2009, Yeong et al. 2014). This morphological response is a notable example of cell totipotency, and it can be manipulated for sustainable seedling production (Wang et al. 2016). Direct regeneration has successfully been employed to produce consistent seedlings from species such as Grateloupia filicina (Baweja and Sahoo 2009), K. alvarezii (Yong et al. 2014b), and Sargassum polycystum (Muhamad et al. 2018) in Provassoli’s Enriched Seawater (PES) or f/2 liquid media for various applications. Although spontaneous regeneration allows for increased seed stock production, supplementing culture media with plant growth regulators (PGRs) and biostimulants enhances direct shoot formation from seaweed explants even more, resulting in a high number of uniform seedlings in a shorter time (Yunque et al. 2011, Hurtado and Critchley 2018). In particular, studies show that incorporating Ascophyllum marine plant extract powder (AMPEP) and PGRs into culture medium promoted thallus growth rate in various Kappaphycus seaweeds for micropropagation under laboratory conditions (Tibubos et al. 2017, Ali et al. 2018b), and that this resulted in increased productivity and valuable traits such as improved carrageenan quality and reduced biotic stress caused by endophytes in the field (Ali et al. 2018a, 2020).

Callus culture

Several previous studies reported the successfulness of inducing and regenerating callus from various macroalgae (Reddy et al. 2008b, Baweja et al. 2009). The main advantage of using plant regenerated from callus culture is the possibility of obtaining new genetic variants, such as plants with higher growth rates due to the somaclonal variation effect (Charrier et al. 2015). Reddy et al. (2003) demonstrated this benefit by comparing the growth rate of micropropagules regenerated from K. alvarezii callus to specimens farmed in India. The study found that the micropropagules restored from the callus have a higher growth rate than the conventionally farmed samples. Many factors contribute to callus formation from seaweed explants, including temperature, light, and PGRs such as auxin and cytokinin used during the tissue culture process (Uji et al. 2016). The seaweed callus may also be used to induce somatic embryos. A study by Mo et al. (2020) shows that somatic embryos can be obtained by culturing Kappaphycus striatus callus in a semi-solid PES medium supplemented with 1 mg L−1 1-naphthaleneacetic acid (NAA) and 2 mg L−1 6-benzylaminopurine (BAP). These somatic embryos were cultured in cool white fluorescent tubes with a light intensity of 55 μmol m−2 s−1 to form new plantlets. However, not all seaweeds are suitable for callus induction. Ramlov et al. (2013) show that Gracilaria domingensis had a higher rate of direct regeneration than indirect regeneration when treated with different PGRs and exposed to different photons fluxes densities.

Protoplast culture

Protoplasts are living plant cells without a cell wall. They have been extensively studied in many fields, such as proteomics, metabolomics, somatic hybridization, cybridization, and protoclonal variation studies (Reddy et al. 2008a). In seaweed tissue culture, protoplast had been used to provide seed stock for cultivation purposes (Gupta et al. 2011, Huddy et al. 2013). Since plant cells are totipotent, many protoplasts can be isolated from a small fragment of seaweed thallus and cultured to produce seaweed seedlings (Huddy et al. 2013). In a few studies, seaweed protoplasts have been shown to regenerate into callus and even whole plants (Huddy et al. 2015, Chen et al. 2018). Using this method, the natural population of seaweeds can be preserved because uniform seedlings can be produced in the laboratory for cultivation. Another advantage of protoplast culture is manipulating seaweed genetics using the somatic hybridization technique (Charrier et al. 2015). Protoplast fusion can be induced chemically with polyethylene glycol or electrically with a cell fusion system. This somatic hybridization technique will allow researchers to create new hybrid strains with desirable traits, such as disease resistance, high yield and quality of colloids, and stress tolerance, challenging to achieve through sexual crossings. Given the fact that much research in this area is needed, the current findings show promising outcomes.

BIOSTIMULANTS AND PGRS FOR DIFFERENT TYPES OF CULTURE

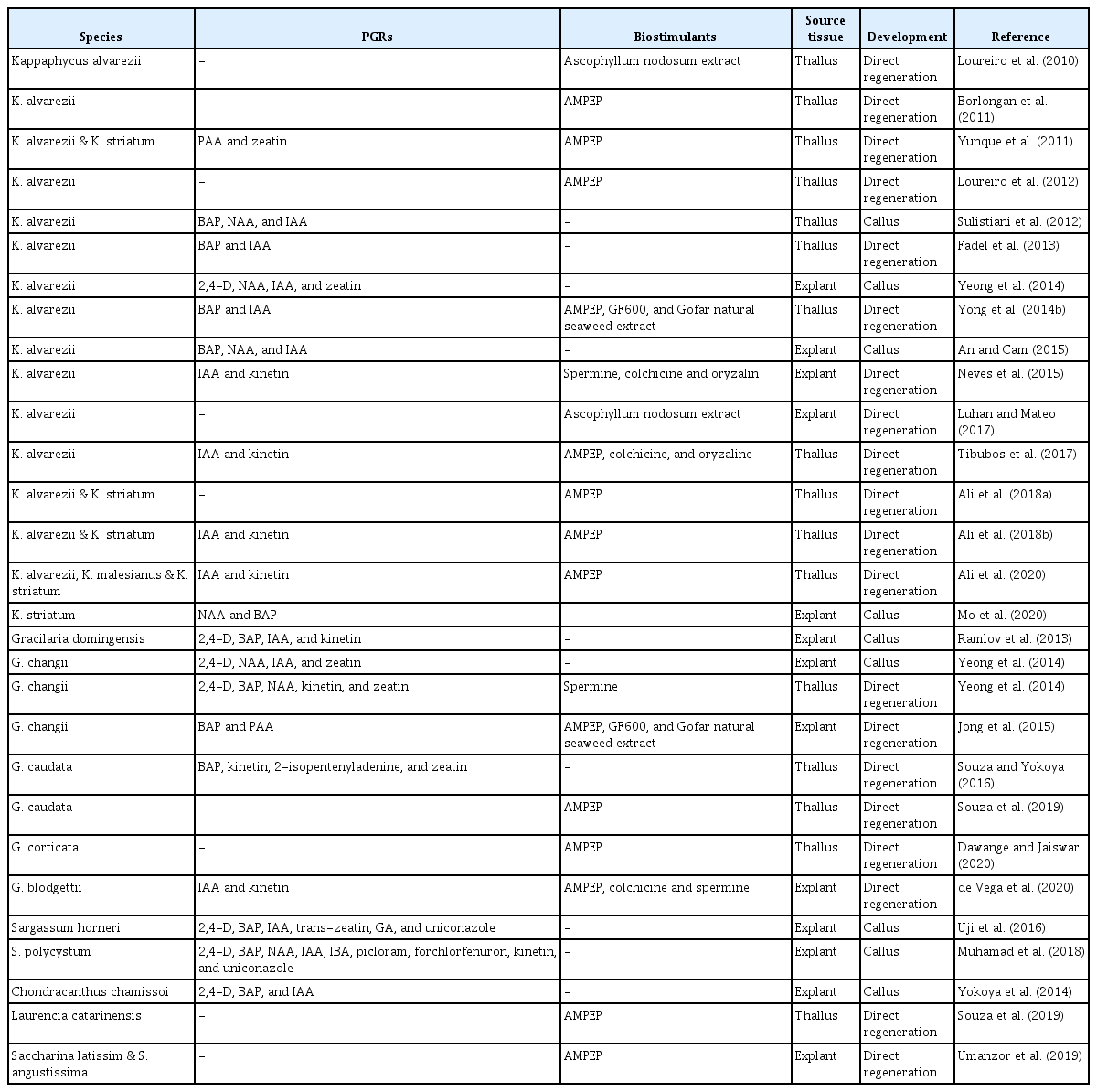

Recent studies have recorded advancements in seaweed cultivation to increase the growth rate and quality of cultured seaweeds. Table 1 summarizes the studies on using biostimulants and PGRs in seaweed cultivation to achieve different types of culture, namely callus induction, and direct regeneration.

Application of plant growth regulators (PGRs) and biostimulants for seaweed seedlings production in the recent decade (2010–2021)

AMPEP and seaweed extracts

The use of seaweed extracts as biostimulant applications in marine agronomy and to benefit increase the growth of other cultivated seaweeds, including eucheumatoids and other species, is currently underway and gaining traction in the seaweed propagation industry (Hurtado and Critchley 2018). AMPEP, a biostimulant made from Ascophyllum nodosum extract, is one of the most widely used biostimulants for seaweed cultivation (Hurtado et al. 2009). Cokrowati et al. (2017) also reported the use of various seaweed extracts, such as Ulva sp., Sargassum sp., and Turbinaria sp., to enhance the growth of eucheumatoid seaweeds. AMPEP was reported to minimize the attachment of epiphytes (Cladophora sp., Ulva sp., and Polysiphonia subtilissima) and their damaging activities in K. alvarezii farming (Loureiro et al. 2010). Another study showed that AMPEP-treated K. alvarezii seedlings had significantly lower Neosiphonia sp. infestation after out-planting in the ocean farm than untreated seedlings (Borlongan et al. 2011). By immersing K. alvarezii in AMPEP solution before practical epiphyte introduction and oxidative burst induction, AMPEP was reported to have a “vaccine-like” effect on K. alvarezii and minimize the oxidative burst effect on the thallus (Loureiro et al. 2012). AMPEP-treated K. alvarezii grew faster, produced more carrageenan, and had a lower oxidative burst effect (bleaching) than untreated K. alvarezii. Loureiro et al. (2012) also speculate on the ability of AMPEP to inhibit the oxidative burst effect due to the presence of betaine in the biostimulant. Aside from Kappaphycus species, Umanzor et al. (2019) discovered that AMPEP improved the growth and thermal tolerance of Saccharina latissima and Saccharina angustissima cultivars in a preliminary investigation. Dawange and Jaiswar (2020) also reported a substantial decrease in antioxidant response in Gracilaria cortica treated with AMPEP, suggesting that this biostimulant possesses potent antioxidant properties. However, the specific components of AMPEP that prevent epiphyte infestation and oxidative stress while also improving cultivar growth rates have yet to be determined.

Auxin and cytokinin

As mentioned in the previous section, PGRs are used in callus culture and direct regeneration. The most common PGRs used in recent seaweed tissue culture studies are BAP, NAA, indole-3-acetic acid (IAA), phenylacetic acid (PAA), 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid (2,4-D), kinetin, and zeatin. The majority of studies have found that IAA, NAA, and BAP are the most effective PGRs for inducing callus in Kappaphycus (Sulistiani et al. 2012, An and Cam 2015, Mo et al. 2020), but PGR application in other genera, such as Gracilaria and Sargassum, has also been well established. However, although a combination of 2,4-D and kinetin has been shown to induce callus in K. alvarezii, no callus was induced in Gracilaria changii under the same conditions (Yeong et al. 2014). These findings indicated that callus formation necessitates different biological requirements in addition to the low potential for callus regeneration in Gracilaria species. Direct regeneration, rather than indirect regeneration through the callus phase, is preferable for micropropagation in this species (Ramlov et al. 2013). Mo et al. (2020) recently reported a study on callus induction in K. striatus using a combination of NAA and BAP after sterilization with silver nanoparticles as an effective disinfectant. To date, there have been only a few studies on the induction of callus in K. striatus, suggesting that the cultivation of K. striatus in solid media poses challenges. Besides, Uji et al. (2016) used uniconazole, a growth retardant, to induce callus in Sargassum horneri. Muhamad et al. (2018) used a combination of uniconazole and kinetin in S. polycystum to achieve the same purpose. In eucheumatoid seaweeds, the use of PGRs, particularly IAA and BAP, has been found to be effective for direct regeneration from seaweed thallus (Yong et al. 2011, 2014b).

Other additives / supplements

Apart from using AMPEP and PGRs to achieve a maximum growth rate in the micropropagation of Kappaphycus seaweeds through the natural regeneration process (Yunque et al. 2011, Ali et al. 2018b, 2020), Tibubos et al. (2017) also used spindle inhibitor (i.e., colchicine and oryzalin) in combination with AMPEP and PGRs to improve direct shoot formation in K. alvarezii. Besides, the biochemical composition and physicochemical properties of Gracilaria verrucosa, such as gel strength, agar viscosity, and nutritional value, were also significantly improved in an independent study using vermicompost fertilizer (Rahim 2018). Based on our review, most research on the use of PGRs and biostimulants in seaweed cultivation focuses on direct regeneration (Table 1). We speculate that direct regeneration is highly preferred due to its cost-effectiveness. Furthermore, direct regeneration produces faster results with less technical inputs and analysis, which is beneficial to the farming community. Meanwhile, as shown in Fig. 2, most PGR and biostimulant studies focus on Kappaphycus, with Gracilaria coming in second, emphasizing research efforts to improve the growth performance of these commercially valuable genera.

Percentage of articles (2010–2021) that reported callus induction and direct regeneration using plant growth regulators and / or biostimulants in a variety of commercially valuable seaweed genera. The analysis was based on a total of 26 recent articles discovered via literature searches on the SpringerLink and Semanticscholar websites. The articles were searched using the keywords “seaweed”, “micropropagation”, “growth regulator”, and “biostimulant”, and manually selected based on the content relevance.

ACCLIMATIZATION OF TISSUE-CULTURED SEAWEEDS

Following lab-scale micropropagation, acclimatization to the outdoor environment is crucial to prepare the seedlings for the grow-out process on the actual farm. During the acclimatization process, the seaweeds are increasingly exposed to environmental stress, such as salinity and temperature variations, as well as direct spectral irradiance. Many studies have shown that acclimatization improves tissue-cultured seaweeds’ survival and growth rate during the grow-out period. According to Yong et al. (2015b), micropropagated K. alvarezii seedlings that were acclimatized in an outdoor tank grew faster in the field (3.91 ± 0.16% d−1) than non-acclimatized seedlings (3.56 ± 0.07% d−1) and were more disease resistant. Since AMPEP supplementation was widely used in the acclimatization study, the presence of beneficial compounds from this biostimulant may help seedlings grow better in the field. However, further research is required to evaluate the benefits and consequences of nutrient supplementation during the acclimatization phase. There has been no study to compare the performance of fertilized and non-fertilized seedlings in the field. Luhan and Sollesta (2010) observed a growth rate increase (up to 34.19% d−1) when the tissue-cultured K. striatus was transferred from a static water-cultivation to a continuous flow-through system. This finding suggests that, in addition to nutrient supplementation, a continuous flow-through system is required to achieve optimal seaweed growth rate during the acclimatization phase. Aside from facilitating nutrient uptake through water movement, the flow-through system may also aid in the removal of any toxic waste released by the seaweed, such as hydrogen peroxide, which is effective and economical for sustainable seedling production. Meanwhile, Rama et al. (2018) discovered that tissue-cultured K. alvarezii grew faster (4.6% d−1) in the field than farm-propagated K. alvarezii (3.5% d−1). In the study, tissue-cultured seedlings were cultivated alongside farm-propagated seedlings for growth analysis. The findings suggest that tissue-cultured seaweeds perform significantly better in the field after tank-based acclimatization with increased thallus regeneration. On the other hand, Budiyanto et al. (2019) discovered that tissue-cultured K. alvarezii can already grow faster (4.3% d−1) in the grow-out phase than farm-propagated K. alvarezii (3.7% d−1) without the need for acclimatization. Comparing these studies, we speculate that the tissue culture process is responsible for the increased growth rate of K. alvarezii in the field, but that the acclimatization process is required to ensure that the seedlings are prepared for the harsh environment. Acclimatized seedlings grow larger and are more ready for field planting, especially since numerous studies on the acclimatization of tissue-cultured Kappaphycus seaweeds have been published in the past decade.

GROW-OUT SYSTEMS FOR ACCLIMATIZED SEEDLINGS

After acclimatization, the seaweeds are grown to full harvesting size during the grow-out phase. Conventionally, seaweed grow-out has been done primarily in a sea-based setting. Several studies have attempted to refine the grow-out process on a land-based system over the last decade, further categorized into pond and tank systems. The grow-out process necessitates a design that keeps the seaweeds in place and prevents them from being washed away by the water flow. In this review, we discovered three systems that were commonly used for the grow-out of eucheumatoid and other seaweeds: (1) open-sea, (2) pond-based, and (3) tank-based systems.

Open sea grow-out system

In an open sea grow-out system for tissue-cultured K. striatus, Luhan and Sollesta (2010) used a rope-fixed method with a 25 cm interval between seedlings. The grow-out system, however, had a lower growth rate (0.05% d−1) than the acclimatization phase in the tank (4.55% d−1), which may be attributed to the high temperature during the grow-out process (recorded as 35.5°C ambient temperature). Kasim and Mustafa (2017) compared the cage-containment and rope-fixed methods in an open sea environment with K. alvarezii seedlings. They found that the cage-containment method produced seedlings with a higher growth rate (3.69% d−1) than the rope-fixed method (2.43% d−1). Seedling damage was also observed in the rope-fixed process but not in the cage-containment process, suggesting that herbivorous attack was the cause of the lower growth rate. The netting on the cage-containment system, on the other hand, protects the seedlings from herbivores. Using the Kappaphycus species, de Góes and Reis (2011) discovered that the tubular-net approach yielded 53.6% more efficiency at planting and harvesting than the rope-fixed method, despite no significant differences in seedling growth rates from both systems. Several studies compared the ability of various substrates to hold Sargassum juveniles during the open sea grow-out process. Aaron-Amper et al. (2020) reached the growth of Sargassum aquifolium juveniles on clay and limestone substrates in the bottom-fixed method and versus nylon rope in the rope-fixed process. The juveniles on clay substrate grew the fastest, with thalli reaching 95.6 ± 37.9 mm at the end of the trial. However, the nylon rope had a higher survival rate than the clay and limestone substrates. On the other hand, Largo et al. (2020) compared the two grow-out approaches using Sargassum siliquosum juveniles. The juveniles grew slower on the bottom-fixed culture using clay and limestone due to fouling and grazing by larger animals such as snails, suggesting the advantage of the rope-fixed method, which reduced biofouling and grazer exposure. Regardless, due to inconsistent research findings, the overall benefits and drawbacks of both bottom-fixed and rope-fixed methods have yet to be determined.

Pond-based grow-out system

The land-based grow-out system has several advantages over the open-sea grow-out system, including easier management of environmental conditions such as water motion, nutrient load, light exposure, and temperature (García-Poza et al. 2020). The land-based system can also protect seaweeds from harsh weather, particularly strong waves that can cause thallus breakage and biomass loss. A pond-based grow-out for tissue-cultured G. verrucosa was conducted by Rejeki et al. (2018), comparing rope-fixed near the water surface, rope-fixed 20 cm from the bottom of the pond, and basket-containment attached to the bottom of the pond for holding the seaweeds. The basket-containment method produced seaweeds with significantly more agar content than other grow-out approaches, suggesting that the lower irradiance exposure at the pond bottom resulted in energy storage in the form of agar. This finding implies that a grow-out system can also be customized to meet the specific requirements of various downstream applications.

Tank-based grow-out system

Cahyani et al. (2020) recently published research on a tank-based grow-out system. They used a rope-fixed method with a continuous flow-through to grow tissue-cultured K. alvarezii from 5, 10, and 15 g initial sizes in a 1,000 L tank. The 5 g seedlings grew the fastest, at 3.76 ± 0.54% d−1, suggesting that the initial size of the seedlings, which had gone through a tissue culture process, influenced the growth of the seaweeds in the grow-out tank. Budiyanto et al. (2019) also discovered that tissue-cultured K. alvarezii grew faster than conventionally farmed K. alvarezii in a grow-out phase where both seedlings started at the same weight. This result implies that tissue-cultured seedlings perform better in tank cultivation, regardless of their initial weight. The rapid growth of tissue-cultured seedlings may be attributed to the high PGRs and macronutrients accumulated in tissues due to tissue culture supplementation. Besides, the increased number of branches in tissue-cultured seedlings may improve their ability to absorb nutrients during the grow-out process. However, when compared to open-sea grow-out, a tank-based system will incur high maintenance costs, particularly when carried out on a commercial scale. A large-scale grow-out system may also face challenges such as limited land area and optimal water supply (Hafting et al. 2012). Rejeki et al. (2018) found that tissue-cultured seedlings grow slower than farm-propagated seedlings in G. verrucosa, implying that the species may not respond well to tissue culture conditions. Due to a lack of research on tank-based grow-out of tissue-cultured Gracilaria, the growth efficiency and yield of tissue-cultured and farm-propagated Gracilaria and Kappaphycus seedlings would need to be verified in the future.

RECENT ADVANCES IN SEAWEED CULTIVATION TECHNIQUES

The growing demand for two important hydrocolloids, carrageenan and agar, has driven global red seaweed farming over the last two decades. The most common red seaweeds cultivated worldwide are Kappaphycus and Eucheuma, which are primary sources of carrageenan, and Gracilaria, which are primary sources of agar (Valderrama et al. 2015). In 2019, 34.7 million tonnes of seaweed products for food and non-food uses generated USD 14.7 billion in revenue, with Kappaphycus / Eucheuma contributing USD 2.4 billion and Gracilaria contributing approximately USD 2.0 billion (Cai et al. 2021). Due to the high demand and profitability of eucheumatoids and Gracilaria, new techniques in seaweed farming have been used to increase the quality and productivity of the seaweed farms, including the use of floating cages in open-sea farming over the conventional longline method to protect seaweeds from grazing predators such as fish and turtles (Kasim and Mustafa 2017). Another novel technique for seaweed cultivation is tube-net cultivation, which was used for Gracilaria dura in open-sea farming along the Gujarat Coast of North West India (Mantri et al. 2020). This method has several advantages, including being less affected by the propelling waves, taking less time to seed, protecting seedlings from drifting, and allowing the depth of planting to be adjusted based on location and season (Mantri et al. 2017a). The economic projections for gross revenue from four harvests per year using this method are US$5,577, while the investment required for the tube-net and related infrastructure is US$1,797, resulting in an estimated profit of US$3,780, or US$11.81 per farmer per day (Mantri et al. 2020).

Though these new cultivation techniques can increase the yield and productivity of seaweed farming, seedling shortages and low-quality planting materials continue to be a barrier to the sustainability of the overall farming industry. This limitation encourages the development of land-based cultivation methods in controlled environments, which have the advantages of adapting to a wide range of seaweed species and forms, and avoiding adverse conditions such as tides, waves, and wind (García-Poza et al. 2020). Although several prominent companies have been practicing it for decades, several studies have been conducted to investigate the critical parameters and technical designs that may improve the yield and efficiency of a land-based farming method. Yu et al. (2013) recorded land-based farming for Sargassum hemiphyllum in a shrimp pond using a rope-fixed method. The weight-specific growth rate of pond-cultivated seedlings was approximately three times higher than that of wild plants. According to the water quality analysis, the nitrogen and phosphate levels in the shrimp pond water were higher than those in the coastal water, which may be attributed to waste excretion from shrimps beneficial to seaweed growth. This farming system could develop a low-cost seaweed cultivation method that relies on shrimp waste as a source of nutrition. Furthermore, an integrated land-based seaweed farming system can become a more environmentally sustainable choice by reducing synthetic fertilizers (García-Poza et al. 2020).

Besides, Zuldin and Shapawi (2015) used vegetative cuttings from an open sea farm, trimmed them to an initial size of 50–60 g, and cultivated them using the rope-fixed method in a continuous flow-through system in an attempt at land-based farming for K. alvarezii and K. striatus with the addition of AMPEP fertilizer. In this experiment, K. striatus and K. alvarezii grew at maximum rates of 2.00 ± 0.03% d−1 and 1.46 ± 0.06% d−1, respectively, which is still lower than the 3.15 ± 0.35% d−1 (Ali et al. 2014) and 3.4 ± 0.3% d−1 (Yong et al. 2014a) growth rates of conventionally farmed K. striatus and K. alvarezii, respectively. This finding may be due to variations in farming location and season, which affect environmental parameters such as temperature, irradiance, and the biochemical composition of seawater. As a result, a parallel study comparing tank-based and open-sea farming should be conducted in the same season and geographical region to verify the growth performance of different farming methods. Aside from environmental concerns, the main disadvantages of land-based cultivation include high infrastructure construction and farm maintenance costs, such as in operative work and energy consumption. While land-based farming may reduce the workload of farmers on open-sea farms, which are often located far from the coast, it will require more technical support than open-sea farming. Moreover, land availability and suitable water for land-based production are generally limited, and even when they are available, they are usually expensive (Hafting et al. 2012). Fig. 3 depicts a flow chart illustrating the various stages of seedling growth prior to the final harvest to summarize recent developments in seaweed seedling production.

PREDATORS, PESTS, AND DISEASES: CURRENT AND FUTURE CHALLENGES

Fish from the Siganidae family were among the recognized seaweed predators, with incidences of feeding on Eucheuma denticulatum seaweed in various habitats (Eggertsen et al. 2019). The production of Kappaphycus and Eucheuma farming in India, particularly on the Krusadai Island, had declined by around 10% due to herbivorous organisms such as Siganus javus (rabbitfish), Acanthurus sp. (surgeonfish), Cetoscarus sp. (parrot fish), and Tripneustes sp. (sea urchin) (Tomas et al. 2011). According to previous studies, herbivorous fish may be attracted to the presence of seaweed fronds at the seaweed farm (Anyango et al. 2017), and fleshy seaweeds were preferred over calcareous coralline and encrusting seaweeds (Tolentino-Pablico et al. 2007). The preferences for seaweed grazing among herbivores are influenced by the availability of food, the presence or absence of secondary metabolites produced by seaweeds for chemical defenses against herbivory, and the nutritional values of seaweeds for consumption (Pillans et al. 2004). Other species that have been seen consuming the farmed seaweeds include amphipods, copepods, and turtles (Peteiro and Freire 2013, Ali et al. 2020).

In addition to predators, pests also threaten seaweed farms, with epiphytic algae being one of the most common pests (Ward et al. 2020). Epiphyte infestation is a common occurrence that is becoming more severe as a result of climate change in several seaweed farming areas, threatening seaweed productivity (Lüning and Pang 2003, Ward et al. 2020). Studies have found that epiphytic filamentous algae minimize the biomass production and carrageenan quality of cultivated Kappaphycus and Eucheuma seaweeds (Hurtado et al. 2006). Epiphytes disrupt photosynthesis process and affect carrageenan formation, as evidenced by the difference in carrageenan yield, with healthy seaweeds having a much higher yield than epiphyte-infected seaweeds (Mulyaningrum et al. 2019). Neosiphonia savatieri accounts for approximately 80–85% of the infesting epiphytic algal species in Malaysia (Vairappan et al. 2008), and it is also the most common species in China (Pang et al. 2015). Epiphyte infestations can be related to abiotic factors influencing the hosts’ fitness, such as salinity, temperature, seawater current, light intensity, and nutrient availability (Hurtado et al. 2006, Ward et al. 2020). Heavy epiphytic algae infections will damage the cortex of seaweeds, rendering the hosts vulnerable to opportunistic bacterial infection, as Vairappan et al. (2008) discovered when seaweeds infested with Neosiphonia apiculata were later infected by Alteromonas, Flavobacterium, and Vibrio bacteria.

Seaweed diseases may be caused by bacteria, protists, viruses, and environmental factors (Ward et al. 2020). One example of a disease that affects the growth of seaweeds is the ice-ice disease. The disease is typically caused by environmental stresses that make the thallus vulnerable to disease-causing opportunistic bacteria, resulting in bleaching of the thallus followed by disintegration of affected tissues (Ward et al. 2022). The bacteria Alteromonas and Pseudoalteromonas, and the Cytophaga-Flavobacterium complex, have been linked to ice-ice disease in infected seaweeds (Ward et al. 2020). In addition to bacteria, marine fungi such as Aspergillus spp. and Phoma sp. were also capable of inducing ice-ice disease symptoms in laboratory-cultivated K. alvarezii and K. striatus (Solis et al. 2010). Another well-studied seaweed disease is the red rot disease caused by Pythium porphyrae (Herrero et al. 2020). Early symptoms include small red patches on infected blades. If the disease progresses, the edge turns violet-red. Multiple holes appear before the entire blade disintegrates from the plants (Ward et al. 2020). All disease problems in commercially domesticated seaweeds must be addressed, as diseases will drastically reduce the quality and productivity of seaweed production, putting seaweed-related industries at risk.

MITIGATION STRATEGY FOR PEST AND DISEASE CONTROL IN SEAWEED FARMING

A few preventive actions can mitigate the adverse effects of pests and diseases in seaweed farming, such as nutritional intervention to make the host stronger by applying a biostimulant / bioeffector or a fertilizer dip treatment before the out-planting stage (Van Oosten et al. 2017), propagation of disease-resistant algal varieties, and introduction of ‘friendly’ microorganisms in the host to counter the pathogen (Gachon et al. 2017). Nutritional intervention has been applied successfully in several seaweed production facilities in the Philippines and Malaysia to prepare Kappaphycus seedlings for out-planting in open-sea farms (Hurtado et al. 2019). This method shows that seaweed extracts or nitrogen treatment before the out-planting stage can reduce the disease and pest infestation rate. A study by Borlongan et al. (2011) shows that dipping the Kappaphycus seedlings in a low concentration of AMPEP (0.1 g L−1) follow by outgrowing the seedling at 50–75 cm below the water surface can significantly reduce the Neosiphonia infestation rate (6–50%) as compared to the untreated seedlings (10–75%). Meanwhile, Luhan et al. (2015) show that immersing the K. alvarezii seedling in a high-nitrogen-containing medium for a short period before out-planting can increased growth, improved the carrageenan quality, and decreased the occurrence of ice-ice disease. In Pyropia, the blades are washed with an acid solution to control all diseases type (Kim et al. 2014). Wang et al. (2014) stated that changing the cultivation conditions, such as repositioning the cultivation ropes to modify light exposure and more favorable salinities, can reduce the severity of disease caused by unfavorable abiotic conditions in Saccharina japonica.

Few studies had previously been conducted in an attempt to overcome epiphytes problems in commercial seaweed cultivation. For example, it has been discovered that the cultivation period and spore culture method of Gracilaria are critical factors in controlling its natural pests (Buschmann et al. 2017, Ingle et al. 2018). It is also suggested that grazers and amphipods, which feed on the epiphytes, be used to control them (Bannister et al. 2019). Lüning and Pang (2003) proposed a high-density seaweed cultivation method to control the epiphytes infestation problem in rope cultures in the sea and seaweed tank cultures on land. The growth of epiphytic algae will be hampered by the cultivated seaweeds in this method because the cultivated seaweeds absorb near all of the light and nutrients. Changing the seasonal rhythms of seaweed cultivation could also aid in epiphyte control (Titlyanov and Titlyanova 2010). Mulyaningrum et al. (2019) proposed a method for controlling light intensity, which promotes the growth of cultivated seaweeds while reducing the presence of epiphytic algae. Another simple but effective method of controlling epiphytes is to apply mechanical movement to the culture lines, preventing epiphyte propagules or spores from attaching at the cultivated seaweed and cultivation facilities (Mulyaningrum et al. 2019). In terms of protecting seaweeds from grazing by other organisms, which is frequently followed by ice-ice disease, the floating cage cultivation method, as used in K. alvarezii and E. denticulatum farming, is promising. This protection system allows for seaweed cultivation with modifications based on farming area topography, as has been done in several cultivation areas throughout the Philippines (Ganesan et al. 2006). It is hoped that this mitigation technique can assist farmers in resolving pest and disease issues while remaining productive in their seaweed farming activity.

CONCLUSION

Seaweed cultivation, particularly eucheumatoids, has progressed considerably over the last ten years. Researchers are incorporating technologies and innovations that take the conventional farming method to the next level, from lab-based cultivation to open-sea farming. A combination of tissue culture and acclimatization was found to improve seedling growth and survival rates during the grow-out and farming stages. Farmers now have a better alternative to farming seaweed, especially in extreme weather conditions, with recent land-based seaweed growing system developments. While land-based cultivation studies have provided several groundbreaking options, their integration into conventional farming is still in its early stages. Further research may be needed to validate the cost-effectiveness of the invented technologies and new techniques in the seaweed cultivation industries. However, based on the promise of the recent development, we anticipate a global revolution in seaweed seedling production in the coming years.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are grateful to the UK Research and Innovation – Global Challenges Research Fund (UKRI-GCRF) for funding the “GlobalSeaweedSTAR” project (GSS/RF/025) and the Universiti Malaysia Sabah for administrative support.

Abbreviations

2,4-D

2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid

AMPEP

Ascophyllum marine plant extract powder

BAP

6-benzylaminopurine

IAA

indole-3-acetic acid

NAA

1-naphthaleneacetic acid

PAA

phenylacetic acid

PES

Provassoli’s Enriched Seawater

PGRs

plant growth regulators

Notes

The authors declare that they have no potential conflicts of interest.